A common aspiration for everyone is to live in a society that offers a fair chance of success to all, where one’s life prospects are not tied to the socioeconomic status of one’s parents. To see how the world has fared by this yardstick of intergenerational fairness, our recent World Bank study analyses economic mobility across generations for individuals born between the 1940s and the 1980s in 148 economies that comprise 96% of the world’s population. Relative mobility measures the relationship between an individual’s position in the income or education scale with his or her parents’ position. The stronger this link, the less relatively mobile (and intergenerationally fair) a society is.

We find that relative mobility is much lower, on average, in developing economies than in high-income economies. For example, 46 out of 50 economies with the lowest rates of mobility from the bottom half to the top quartile of the education ladder are in the developing world; and all 25 economies in the bottom third by relative mobility in income are developing economies. The poorest regions of the world, sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, are also the least mobile. Average mobility of these two regions and of Eastern Europe and Central Asia has not improved since the 1950s generation, in contrast with the gradual improvements seen for other developing regions and high-income economies.

Improving intergenerational fairness in developing economies

Which policies can improve intergenerational fairness in developing economies? Importantly, policies that promote economic growth are good for mobility, since growth increases the size of the economic pie and generates greater resources for public investments. But higher growth may not necessarily lead to higher relative mobility, as the experiences of several emerging economies (including China and India) illustrate. Lower relative mobility is associated with higher inequality, as the two tend to reinforce each other. To break this vicious cycle the state needs to play a proactive role in promoting inclusion – reducing inequality of opportunities among individuals born with vast differences in “starting points” i.e., the circumstances they are born into.

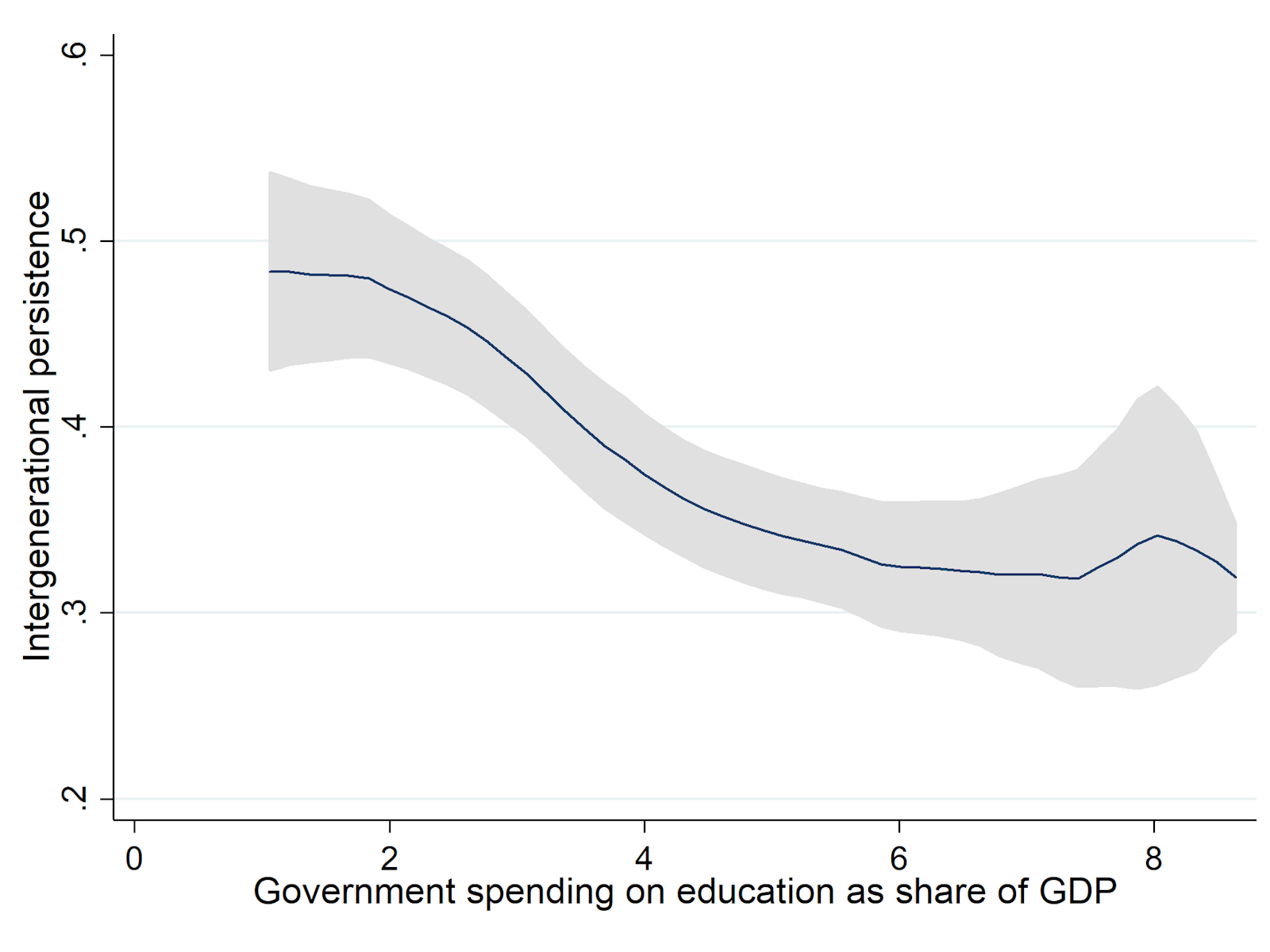

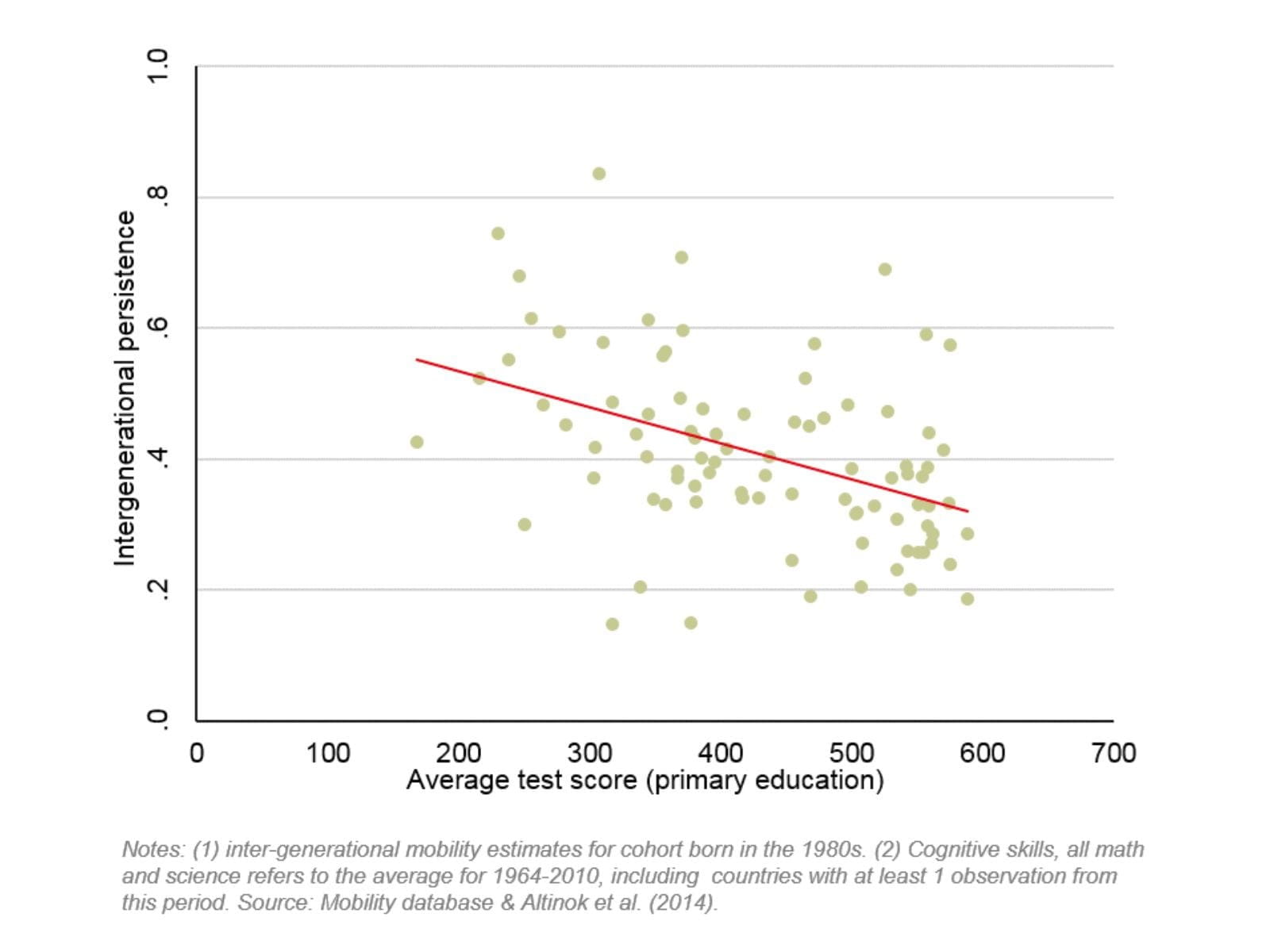

Policy interventions to narrow opportunity gaps need to start early in life by targeting maternal health and early childhood, since gaps that emerge then are difficult and costly to close over time. As children get older, the education system must focus on closing gaps in access and learning between the haves and have-nots (see this World Bank report). Relative mobility in education tends to be higher in countries that invest more public resources in education relative to the size of their economy (Figure A). Mobility is also higher when spending is more effective – when fewer children are out of school, teacher-student ratios are higher, and learning outcomes are better for primary school-age children (Figure B).

Higher intergenerational persistence: lower relative mobility

Source: Figure 4.12(b) in Narayan et al (2018), 'Fair Progress? Economic Mobility Across Generations Around the World'. World Bank.

Source: Figure 5.3(c) in Narayan et al (2018), 'Fair Progress? Economic Mobility Across Generations Around the World'. World Bank.

Governments need to be proactive about equalising opportunities across space. Economies (and regions within economies) with greater geographic segregation in educational attainment are likely to have lower mobility. Evidence from other research suggests that interventions to improve local environments – reducing socioeconomic segregation, investing in services and infrastructure, and building social capital – are likely to be beneficial for intergenerational mobility, and particularly so among the generations who experience these changes at an early age.

The importance of functioning fiscal systems and labour markets

The fiscal system has a key role in promoting mobility by reducing the gaps in starting points for individuals (direct redistribution) and mobilising resources to finance “equalising” public investments. Doing so without imposing too high a cost on economic efficiency requires increasing progressivity of taxes and broadening the tax base through less distortionary means – such as property, wealth and inheritance taxes – and strengthening tax compliance. Lower tax revenue and a smaller share of direct taxes in total revenue (or a less progressive tax structure) are found to be associated with lower relative mobility. Redistributive transfers and tax credits to poor families can help enhance their human capital investments.

“We need a better understanding of the distribution of resources, the investment needs, the management of existing assets and the generation of public revenues.” (ICAEW Intergenerational Fairness Survey 2017)

Economic mobility also depends on the functioning of markets that determine job creation and earnings. If economic opportunities do not keep pace with the expectations of citizens as education levels rise, societies may come under growing stress. Weak labour markets are important reasons why income mobility is lower in many middle-income economies, including several in Latin America and the Middle East, than would be expected for their levels of educational mobility. Improving labour markets would require policies to enhance job creation and competition among employers, protect workers against discrimination, and ease the access of lagging groups including women and youth to labour markets.

In designing policies, governments need to recognise that raising intergenerational mobility addresses a society’s aspirations for not just fairness, but also long-term prosperity. In a society with greater relative mobility, productivity is higher as human potential is used better and rewards are aligned more closely to individuals’ abilities rather than their inherited privilege, which is good for economic growth. Fairness and economic prosperity, therefore, can be mutually reinforcing policy goals, rather than being a choice between two competing objectives.

Interventions to improve local environments are likely to be beneficial for intergenerational mobility.