While the partnership model has been the preferred choice of accountancy practices’, some are questioning whether other ownership structures might offer better options for firms in the future.

Professional services firms in the UK are able to incorporate and trade as limited companies, but the vast majority choose not to do so. Instead, most have opted to remain as partnerships, following an ownership model that has evolved only gradually since the Victorian era.

One reason for questioning the model is that there are disincentives to retain profits for investment in the business at a time of huge upheaval. Matthew Rourke, former Managing Partner with private equity house HgCapital, explains: “The problem is how to align the interests of older partners, who want to maximise their income now, and younger partners who want to invest in future growth.”

He adds: “I don’t see the next generation wanting to buy into a partnership on the assumption that they will be working on the business over the next 15 or 20 years.” The 2016 Global Survey of Millennials, for example, found that one in four millennials planned to quit their job in the coming year.

Rourke had a hand in setting up CogitalGroup, a global business services group, and now invests his own funds through CowCorner, a private investment business based in Sussex. One of its investments is Galloways, a local accountancy practice that now operates as a limited company.

“The partnership model doesn’t work for all businesses in this industry,” Rourke says. “The opportunity for expansion is limited. Value creation is more straightforward in a corporate model.”

The argument is, essentially, that if the interests of individual partners are paramount, the interests of the business as a corporate entity may be less of a priority.

Pressure on the big firms

If these are the factors putting pressure on partnership for smaller firms, what about the other end of the market?

One issue is the prospect that regulators in the UK and elsewhere will demand that large firms’ audit and non-audit arms need to operate as separately managed entities.

The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority called for this in 2019 and, in February this year, the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) urged firms to make the adjustment ahead of any legislative change. The creation of separate entities might be seen as an opportunity to set up a corporate, rather than a partnership-based, structure.

Meanwhile, margins at the Big Four firms are coming under pressure, argues Shamus Rae, a former KPMG Partner who is now CEO of Engine B, a consortium set up to solve obstacles to the digitisation of professional services.

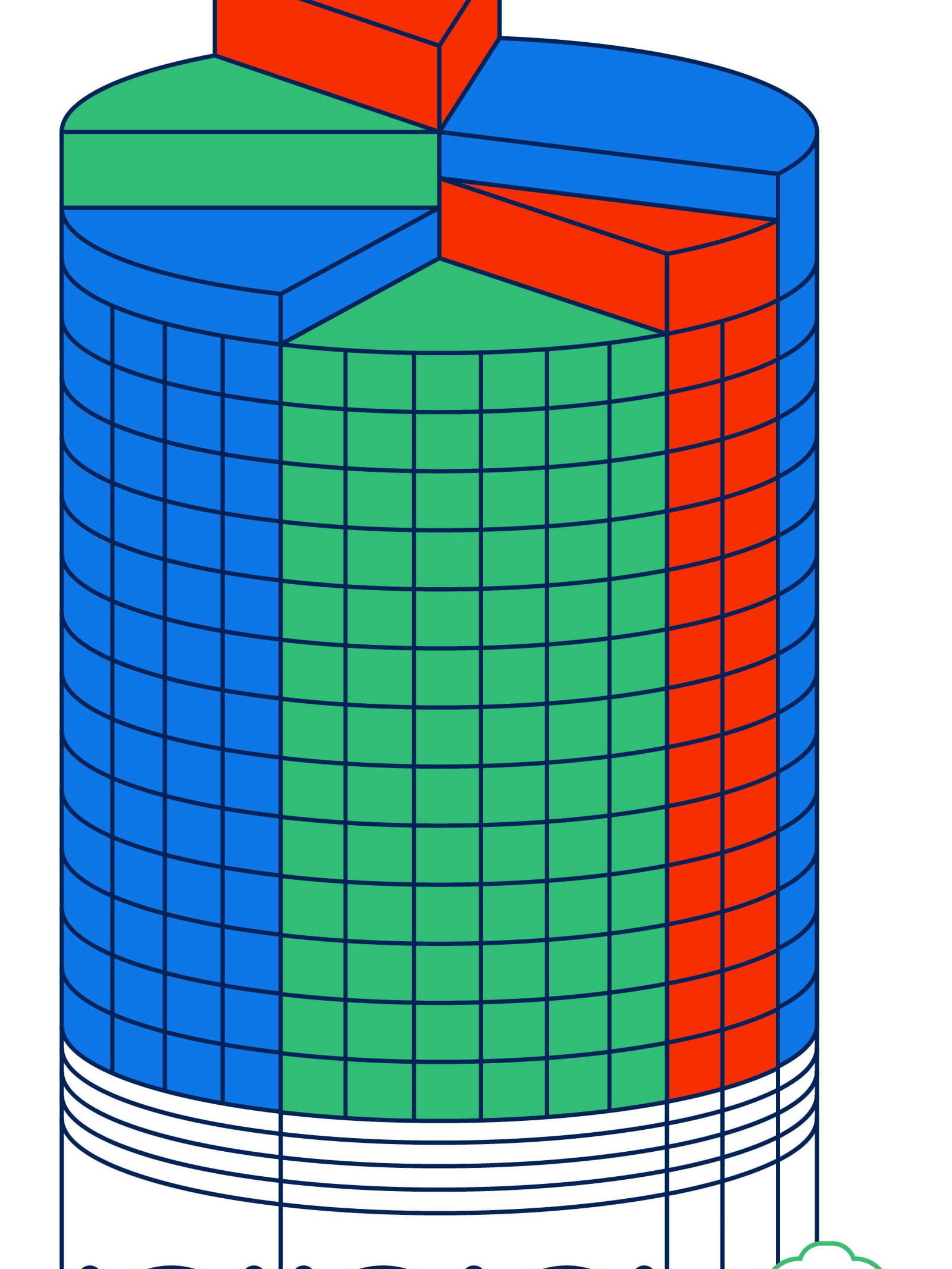

Margin Decline in the Professions, a report produced by Engine B, shows that the average profit margin for the Big Four has declined steadily from 30% in 2006 to 18% in 2019. At the same time, revenue per employee went up by 23%, compared with 46% for UK inflation, as measured by the Bank of England.

A margin of 18% still looks better than average for the UK services sector (Office of National Statistics, 14.9% in Q4 2019) but the direction of travel is arguably problematic.

So far, Big Four profits per partner have been protected by squeezing partner/staff ratios, from 1:19 in 2006 to 1:26 in 2019. That, Rae says, is not sustainable. “There is no more kicking the can down the road.”

The issue of tech investment

Increasing productivity must be the solution, and that means investment in technology. Rae is not convinced, however, that a typical professional partnership is geared to addressing the issue.

He says: “Is the partnership model, which is one of collective (or pseudo-collective) decision-making, one that will actively discuss which service lines are going to be disrupted by technology? Are they going to invest this year’s money for the benefit of next year’s partners? And are they willing to sign off on a change in the business model that might not include them being part of the business in future?”

Engine B’s proposed answer for the technology issue is to develop industry-wide standards for sharing corporate data, so that solutions can be developed that are available to every firm.

The last dramatic change in the sector took place in the early 2000s, following the Limited Liability Partnerships Act (2000). Prior to that, accountancy firms had typically operated as partnerships under the 1890 Partnership Act.

The main appeal of the limited liability partnership (LLP) was, as the name suggests, that it offered limited liability as opposed to the joint and several liability of the traditional partnership, at a time of growing negligence claims.

Now, the vast majority of firms – at least those from the middle tier upward – are LLPs. For example, the FRC’s 2019 report Key Facts and Trends in the Accountancy Profession lists 30 firms with public interest entity (PIE) audit clients. Of these, 18 are LLPs and seven are partnerships. Three are limited companies, with one, Haines Watts, being a mix of different structures; and one is a sole trader.

Similarly, the Accountancy Age Top 100 UK firms by fee income is dominated by LLPs, with few exceptions. TaxAssist operates on a franchise basis with a corporate structure at its head, while Smith & Williamson is in the process of being acquired by wealth management group Tilney.

The 20 largest UK law firms by revenue are also all LLPs, with the exception of Slaughter & May, which is a traditional partnership. None of the leading UK law firms has a limited company structure.

The advantages of LLPs

While both the limited liability company and LLP models offer limited liability (in contrast to a general partnership), the LLP format has a number of advantages when compared with a limited company structure. The members are taxed like partners (on their share of the profits); it’s flexible (profit shares can be agreed as seen fit); the partnership agreement is private (in contrast to the articles of a company); and there are no capital maintenance requirements.

Jos Moule, Head of Partnerships and LLPs with law firm VWV, says: “For an LLP, the main advantage is tax. A limited company format can be good for a small business, but when the practice grows it can be difficult transferring shares as principals leave or join.”

The tax situation is complex, but essentially the key difference for taxation is that an LLP is tax-transparent – that is, the partners rather than the corporate entity are taxed. Depending on the firm’s circumstances, either a limited company or an LLP format might be more suitable. For example, a limited company allows more flexibility over the timing of tax liabilities. But, in many cases, the difference between the two is marginal.

One issue that might change the popularity of the LLP is consolidation within the professional services sector.

One of the new breed is the Xeinadin Group. Describing itself as “the firm of the future”, the London-based group has acquired practices throughout the UK and Ireland. Xeinadin itself is a limited company and, while it operates much like a network of firms, its structure is wholly corporate.

Chief Operating Officer Nigel Bennett says: “The advantages of consolidation are pretty well documented, with economy of scale, partnerships and the ability to better serve larger clients with the resources of a group that can challenge the Big Four. We’re able to share best practice throughout the group, with Xeinadin having a particular focus on technology and innovation.”

Bennett says that Xeinadin is currently self-funded, with close to nil debt. Further consolidation, he says, will be targeted to improve geographical coverage and to strengthen the group as a whole with businesses that have complementary skills.

“Buying up firms is cheaper than organic growth,” says Gordon Gilchrist of 2020, a consultancy firm that advises professional services businesses. He adds that one of the factors driving consolidation is the need to invest in technology, and particularly in cloud-based accounting.

As he puts it: “The cost is not so much the software as the training involved. For the younger generation, their use of technology is seamless. Training, for older accountants, can be quite onerous.”

Philip Shohet, a Senior Consultant with Foulger Underwood, says succession is another factor that encourages consolidation: “It’s a substantial issue finding succession for a practice, even from within. There is a distinct possibility that we will see a contraction in the number of accountancy practices, especially in the middle tier.”

In order to realise the value of the business, departing partners need to bring in successors with new capital. Otherwise, partners looking to retire may have to consider selling the business.

Even so, Shohet believes that accountancy is a good prospect: “It’s a good sector if you invest in a practice that has a vision of where it wants to go.”

Lorraine Twist, a director with recruitment specialists Hays, argues: “There is certainly a desire by ambitious, driven individuals to achieve partnership. But not everyone wants to be partner – that is how the system works.”

She believes that the next generation of potential partners is looking for slightly different things from partnership, and the firms themselves are changing to accommodate them, with less hierarchical structures and more flexible working.

The appeal of the “consolidation” strategy and the decision-making focus that a corporate structure allows are arguably reasons to look again at alternatives to partnership. The arguments for the status quo, however – particularly the simplicity and transparency of the LLP as far as tax is concerned – are strong too. For many professionals there is also an appeal in the collegiate ethos of a partnership.

For some firms, incorporation might turn out to mean greater access to finance, but that is not the most pressing issue, compared with the bigger question: is the firm being managed in the long-term interests of the business, or of the individuals in the business?

It’s a question that many will be pondering in the years to come.

Know your limits

The key distinctions between traditional partnerships, LLPs and limited companies have always been about tax, professional regulation and limitation of liability. The move en masse to the LLP format was driven by the latter.

The large accountancy firms, particularly, had been eyeing a move to LLP structures already available in Jersey and Guernsey because their partners were well aware of the implications of joint and several liability. For the UK government, such a move offshore would have threatened tax revenues.

VWV’s Jos Moule points out that, given that both limited companies and LLPs offer limited liability, for a firm the decision as to which to pick will largely depend on the tax implications. These aren’t always clear-cut.

He stresses: “For most professional practices, the LLP generally offers a more flexible tax structure. While a limited company may initially appear to offer certain tax advantages over LLPs, the benefits can be very marginal, particularly when weighed up against some of the downsides.”

Particular areas to lookout for are the implications when a firm grows, or when principals leave and are replaced. This can be more difficult for a limited company because the shares held are treated as taxable assets and the rules covering employee-owned shares, in particular, are complex.

In contrast, a “share” in an LLP is simply the bundle of financial, voting and other rights rather than being an instrument in its own right. This means that the same difficulties do not arise.

- Top 5 professional indemnity claims for accountants in 2025

- Getting to grips with GenAI for Practice

- 2026: Companies House and start of AML supervision changes

- Acting Office: ICAEW Technology Accreditation – The New Standard of Fully Integrated Practice Technology

- AML Supervisory Reform: Navigating the Road Ahead