Technological innovation and digitalisation are revolutionising tax reporting. This could be of great benefit to business and the public but many genuine concerns remain; we take you through them.

Back in 2015, the government announced its programme to digitalise the tax system: Making Tax Digital. And despite the completion date drifting, HMRC has repeatedly committed itself to delivering more frequent fiscal reporting.

The aim is to facilitate tax payments by building an automated high-quality information feed and by unifying all tax communications in a single online account. And more timely fiscal data should enable improved compliance and economic monitoring by HMRC. An income tax pilot is underway and, over time, HMRC plans to expand MTD to include other business taxes.

However, there have been several delays. The latest delay, announced by the government in December 2022, cast doubt on the MTD project being completed by 2030. “There is now no start date for MTD income tax self-assessment for partnerships nor for MTD corporation tax; they are unlikely to be delivered this decade,” wrote Caroline Miskin, ICAEW senior technical manager in digital taxation. “To make the implementation of MTD income tax self-assessment manageable, HMRC seems to be relying on the much smaller numbers of taxpayers that will be mandated to use it from 2026 and 2027.”

Despite problems with the rollout of MTD, the UK is one of the world’s most digitalised tax regimes. ICAEW’s Digitalisation of Tax: International Perspectives report summarises the progress of tax authorities abroad.

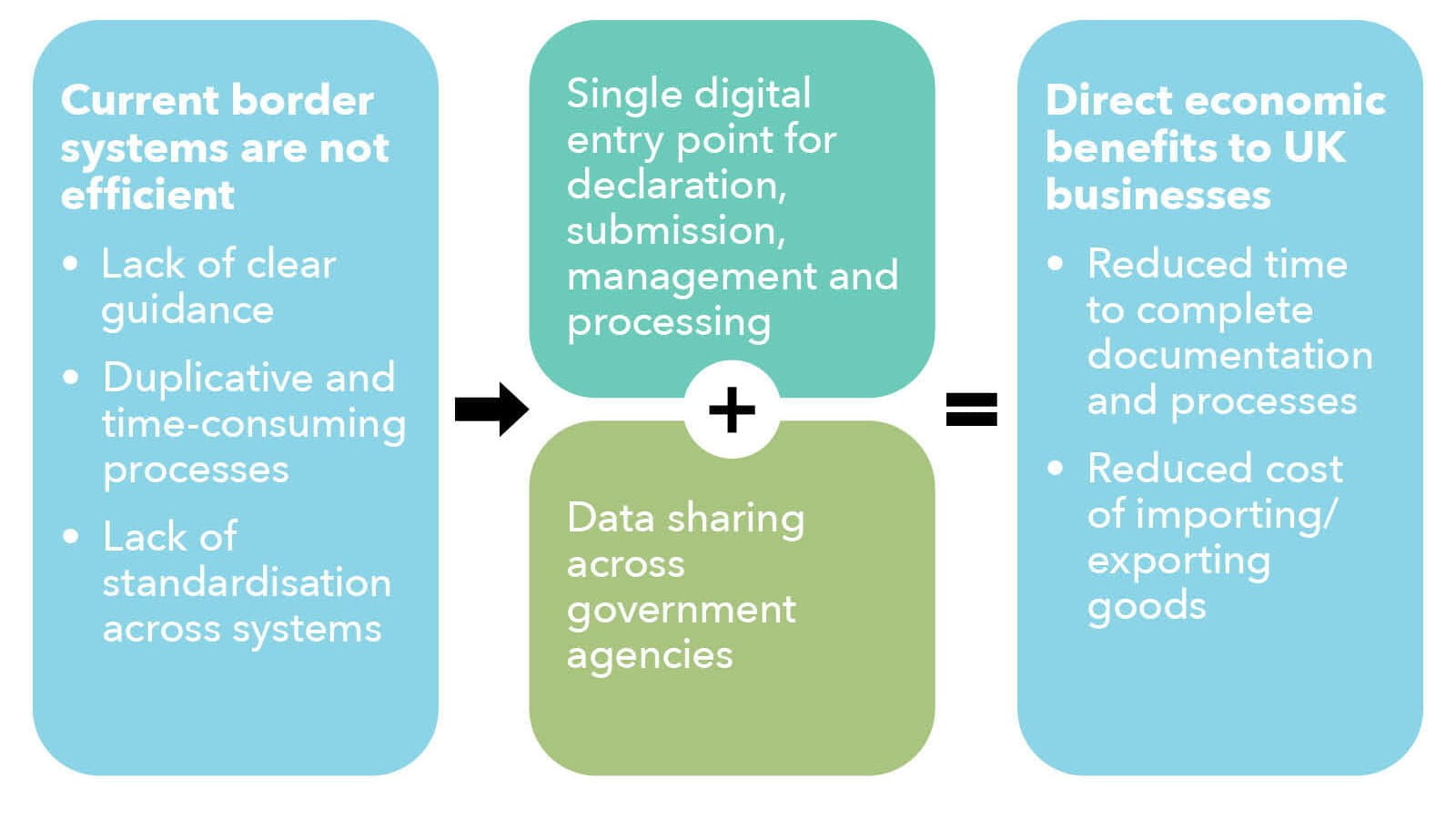

As jurisdictions digitalise their tax systems, they benefit from higher frequency tax reporting and increased data sharing across government departments. In the UK, one example is the development and rollout of the Single Trade Window, which aims to enable importers and exporters to complete just one customs filing, and which typifies a government trying harder to connect its databases.

Moving goods across the UK border currently involves multiple systems – some duplicative – creating extra complexity and cost. Now, the government is investing £180m to provide a single portal into which border user data needs entering just once. The Single Trade Window is also intended to improve data sharing among government agencies.

Benefits and challenges

The twin goals of digitalisation, then, are to improve the quality of fiscal data for government departments while easing the bureaucratic burden of tax collection for businesses and private individuals. The Better Than Cash Alliance also says that it anticipates public trust for tax authorities rising because of the increased transparency that digitalisation brings.

While digitalisation has many benefits, though, it poses numerous challenges as well. “Some can be worked on, such as taxpayer reticence,” notes ICAEW, “but issues such as digital exclusion will always be with us. Some taxpayers are unable to keep up with changing requirements due to an inability or unwillingness to use digital methods…[with] a multitude of reasons for this exclusion, such as a lack of digital skills, distrust of online interaction, remote location away from reliable internet infrastructure, poverty or disability.”

Digitalisation can be challenging for firms and individuals alike. Accenture reports that around 14% of the UK population is ‘digitally excluded’, meaning they either lack access to the necessary technology or are not confident in using it to conduct matters, financial or not, online.

“While the majority of UK citizens are able to participate in the digital world, there is a sizeable minority for whom access is more problematic,” says Accenture’s Mark Jennings. “At the most acute end of the spectrum, our research shows that 3% of UK citizens say they do not use the internet at all. That would equate to around 1.65m adults.”

A digital tax system will face considerable limitations if millions of taxpayers are unable to use it. “Tax authorities have sought to maximise the uptake of digitalised reporting and payment methods, most commonly by making them mandatory,” says ICAEW. “Yet for the digitally excluded, this can be painful or unfair to those with specific disabilities. There is no complete solution to the issue of digital exclusion, but it remains a key consideration for any digital development programme.”

The corporate sector has issues with digitalisation, too. “While companies are happy to automate and save costs on their tax compliance, the impetus for most digitalisation comes from national tax authorities and their evolving requirements rather than organically from within the taxpayer ecosystem,” says ICAEW.

The mandating of technology has raised several concerns in business. As well as the anticipation of increased burdens and costs, real-time tax reporting is regularly framed as a ‘data grab’ that could imperil the fine line between automation and privacy.

Corporate disputes and data privacy concerns

EY’s Luis Coronado has conferred with colleagues dealing with tax controversy (audits, disputes, and litigation, etc.) in 17 of the world’s major jurisdictions. As authorities’ resources are ploughed into extra scrutiny, he sees “overwhelming evidence that there is but one trajectory for tax controversy globally in the short-to-medium term – upward”.

Many large multinationals who responded to the 2021 EY Tax Risk and Controversy survey say they have experienced “aggressive” tax authority behaviour in the past three years. Companies describe many data requests “completely unreasonable” or even “intrusive”, and say that the scope, relevancy and time given to respond to enquiries are all challenges.

“Tax authority digitalisation is disrupting the decades-old tax compliance life cycle, [with] many companies feeling behind the curve. Automated fines or penalties for incorrectly formatted or mismatched data can quickly mount, and many companies have said that simply keeping up with the growing volume of automated infraction notices is creating a significant resource strain on the tax function,” says EY.

Ongoing compliance with digitalisation is expected to be expensive, too. A separate 2022 EY survey of 1,650 executives in more than 40 jurisdictions and 12 industries also found that 59% of respondents believe that complying with emerging digital fiscal filing requirements will raise finance function costs. The majority of those surveyed also foresee more audits, new disclosure requirements and extra transparency demands, as well as increased staff training costs.

Finally, there is apprehension over the security of government-held fiscal data. “Tax administrations must control how they share and protect data, to build taxpayers’ confidence in the privacy and proper use of their data, and to avoid distrust that can lead to lower compliance with reporting and other tax obligations,” says Dr Jay Rosengard, lecturer in public policy at Harvard University. “Positive examples include the UK and South Africa, which only make the data available in ‘data laboratories’ – controlled environments that prevent potential leaks or misuse of taxpayer data.”

Granted, the UK government has outlined the risks in its Parliamentary Post 664 on public data sharing by saying: “Privacy-enhancing technologies can mitigate the risk of privacy breaches, for example by using advanced data encryption.” However, it cautions that: “many experts note that it is difficult to predict and mitigate against future motivations or technologies that could violate privacy. Some privacy experts say that collection and sharing of public sector data, particularly personal data, should be minimised not increased.”

Governments will need to maintain strict safeguards to protect citizens and businesses from such risks. Especially as, on the horizon, there is the threat of quantum computers powerful enough to break public-key encryption. To maintain the security of, and public trust in, digitalised tax systems, authorities will need to invest in ever-more sophisticated technology to protect user data.