The ICAEW chart of the week is on the results of the General Certificate of General Education (GCSE) in mathematics for the past four years in England according to the Department for Education (DfE), illustrating how a burst of grade inflation in the pandemic poses challenges for both students and their examiners in the reinstated examinations this summer.

Maths is one of the core exam subjects taken by almost all 16-year-olds in England, with passes at grade 4 or above in both maths and English being a base requirement for most students wanting to progress onto GCSE Advanced (A level) courses and to university or a degree apprenticeship after that. It is also a prerequisite for many vocational qualifications, where good numeracy skills are often essential.

The current grading system was adopted in 2017, with results now split into nine grades, which can be grouped into three categories of three grades each: below standard (1-3), good performance (4-6) and high performance (7-9). The four former grades of G, F, E and D were condensed into three (grades 1-3), while the old passing grade of C and the next level up of B were expanded to three, being 4 (pass), 5 (strong pass) and 6. The former high performance grades of A and A* were replaced by grades 7, 8 and 9, providing even more granularity at the top end.

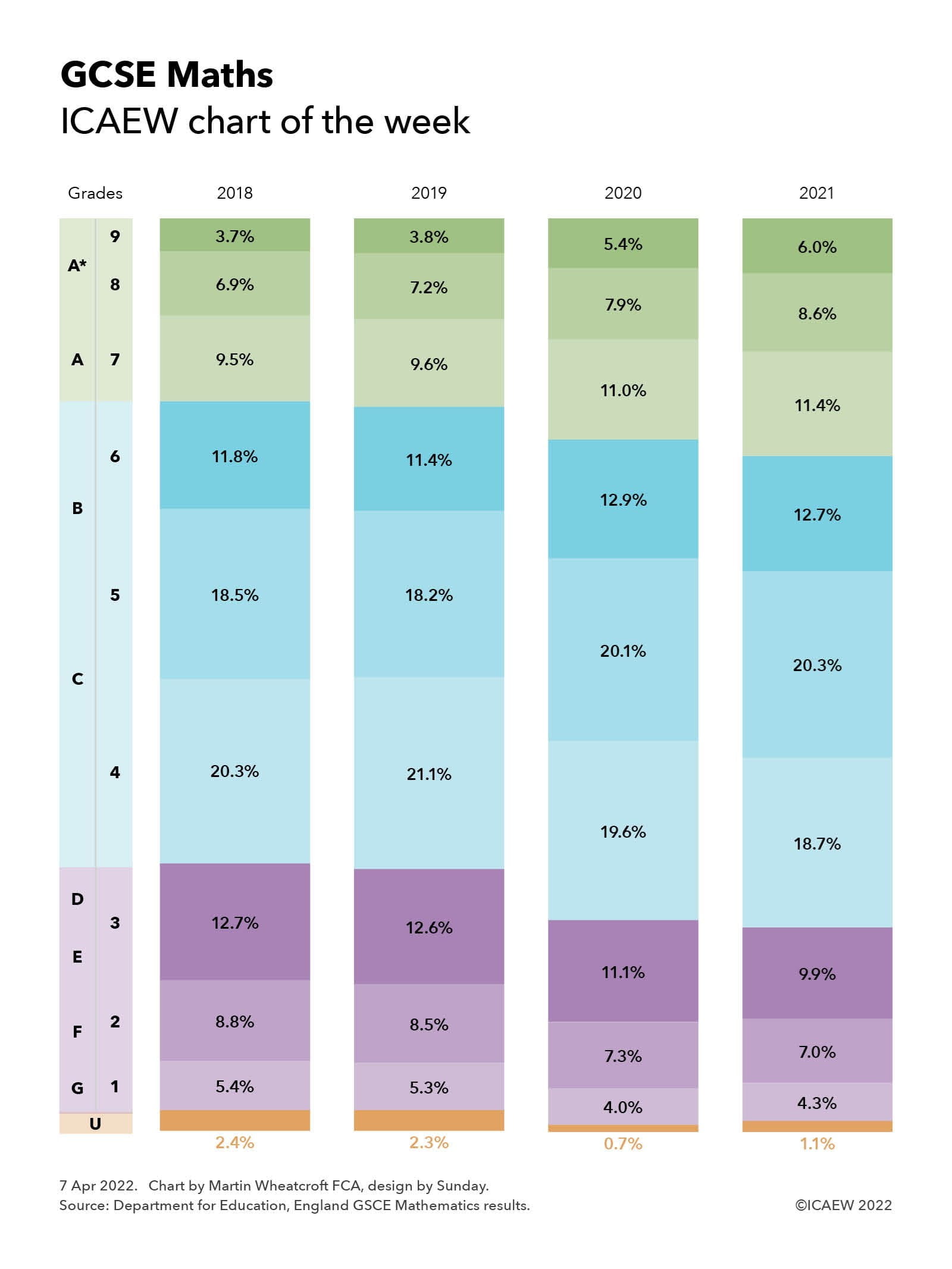

The chart illustrates how before the pandemic the results in 2018 and 2019 were similar with 2.4% and 2.3% ungraded ‘U’ results respectively (which includes those who failed to turn up or who withdrew after entering), with respectively 26.9% and 26.4% of students receiving below standard grades (1-3), 50.6% and 50.7% received good performance grades (4-6), and 20.1% and 20.6% received high performance grades (7-9).

The debacle of the cancelled school examinations and regraded results in 2020, and the deliberate decision in 2021 to adopt teacher-assessed grades instead of exams, saw a significant rise in the number of higher grades awarded. There were fewer ungraded results (0.7% in 2020 and 1.1% in 2021), fewer below standard awards (22.4% and 21.2% respectively), more good performance grades (52.6% and 51.7%) and a great deal more high performance grades (24.3% and 26.0%). There was a big jump in the very top award, the so-called A**, with 6.0% of students receiving grade 9 in 2021 compared with 3.7% in 2018.

The percentage of each grade awarded by year were as follows:

2018 – U (2.4%), grades 1-3 (5.4%, 8.8%, 12.7%), grades 4-6 (20.3%, 18.5%, 11.8%), grades 7-9 (9.5%, 6.9%, 3.7%) – 535,312 entrants

2019 – U (2.3%), grades 1-3 (5.3%, 8.5%, 12.6%), grades 4-6 (21.1%, 18.2%, 11.4%), grades 7-9 (9.6%, 7.2%, 3.8%) – 554,598 entrants

2020 – U (0.7%), grades 1-3 (4.0%, 7.3%, 11.1%), grades 4-6 (19.6%, 20.1%, 12.9%), grades 7-9 (11.0%, 7.9%, 5.4%) – 571,624 entrants

2021 – U (1.1%), grades 1-3 (4.3%, 7.0%, 9.9%), grades 4-6 (18.7%, 20.3%, 12.7%), grades 7-9 (11.4%, 8.6%, 6.0%) – 584,933 entrants

The Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual), which regulates qualifications, examinations and assessments in England, has expressed a desire to return to a pre-pandemic grade profile but has acknowledged that the current cohort of GCSE students have experienced significant disruption to their education over the past two years. As a consequence, they believe it would be unfair to revert back to the previous level awards in one go and have said that they will set grade boundaries around the mid-point between the 2019 and 2021 results, subject to the normal process of moderation.

This may seem unfair to students who can expect to be rewarded with less generous marks than their immediate predecessors given the difficulties being experienced in many schools over the past two years as they have studied for their GCSEs. There have been frequent closures and class disruptions as the coronavirus has and continues to propagate around the country. But Ofqual and the examiners are keen to avoid the grade inflation experienced over the last two years of teacher-assessed grades becoming embedded, a real prospect if they were to wait another year or two before attempting to bring grades back down towards pre-pandemic levels.

The experience of the last two years is that the ability of Ofqual and the DfE to deliver their plan will depend on events, so we will need to wait to see how well the process of sitting exams goes and how the results when they are announced are viewed by the court of public opinion.

In the meantime, we wish all the best of success to all those studying for their GCSEs this summer in England, as well as to their compatriots sitting equivalent exams in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.