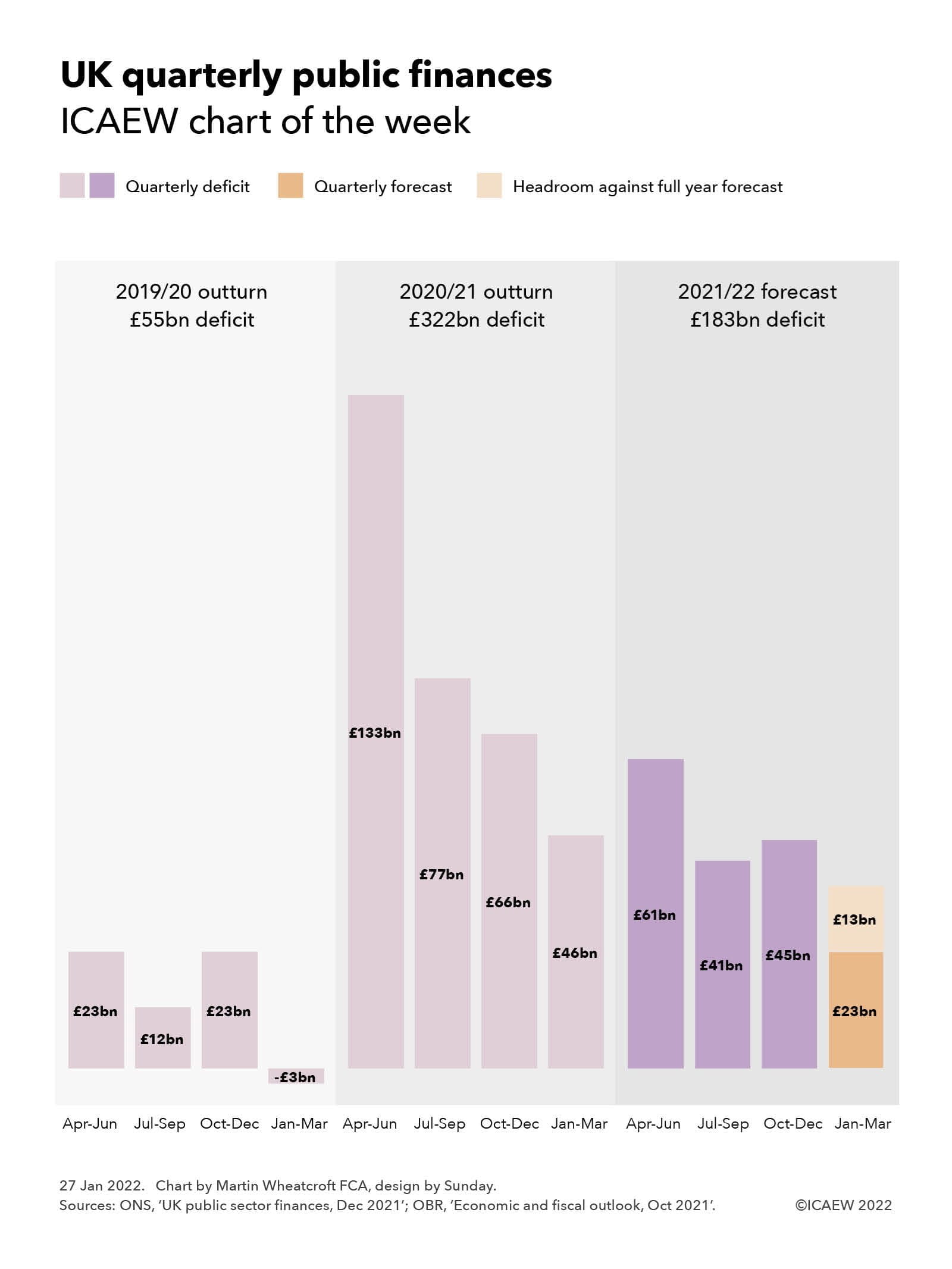

The December 2021 public sector finances published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) on Tuesday 25 January provided numbers for the first three quarters of the current financial year. As our chart this week illustrates, this leaves the final quarter still to go, with £13bn of headroom against the official forecast prepared by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) at the time of the Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021 back in October.

To put the current fiscal year into context, our chart shows how the deficit of £55bn in 2019/20 comprised quarterly deficits of £23bn for April to June 2019, £12bn for July to September 2019 and £23bn for October to December 2019 less a surplus of £3bn for January to March 2020. Although there was some impact from the pandemic on the last month of that financial year, it broadly provides an indication of a ‘normal’ pattern of deficits across the year, with the second quarter and more especially the fourth quarter benefiting from self assessment tax receipts – the latter despite typically higher levels of capital expenditure in the run up to the end of the financial year.

This was followed by the first full year of the pandemic and associated lockdowns which saw tax receipts fall significantly and expenditures rise dramatically, resulting in an unprecedented peacetime deficit of £322bn in 2020/21, comprising £133bn, £77bn, £66bn and £46bn for the four quarters respectively.

The current forecast is also on course for a pretty eye-watering deficit, which despite being substantially below that seen last year is forecast to be as much as £183bn. The provisional numbers for the first three quarters of 2021/22 of £61bn, £41bn and £45bn respectively are currently £13bn below the October forecast, implying an equivalent amount of headroom for the final quarter, assuming the OBR’s forecast deficit of £23bn for the fourth quarter proves to be accurate.

In practice, it would be surprising if the fourth quarter did come in on target other than by coincidence. Better than expected tax revenues are expected to continue to reduce the deficit over the final quarter but this is likely to be offset to a greater or lesser extent by higher interest costs on index-linked debt driven by rising inflation. There are also significant uncertainties around expenditures given the continuation of pandemic restrictions into January and the potential for further interventions to support businesses and individuals struggling financially as a consequence.

There have been suggestions that this headroom of £13bn is a ‘windfall’ that the Chancellor should use to support households expected to be hit by a greater than 50% rise in energy prices from April 2022 as discussed in last week’s chart of the week.

However, this perspective has also been contradicted by Carl Emmerson, Deputy Director at the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), who is reported to have commented: “While borrowing last month was in line with the Budget forecast, over the first nine months of 2021/22 it is now £13bn below that forecast for the same period in the October Budget – £147bn instead of the £160bn expected in October. The latest improvement to borrowing over this period has been driven by higher-than-expected corporation tax being paid by some very large companies.

“Some have suggested better borrowing figures provide the Chancellor room to act on the cost of living by, for example, delaying the rise in National Insurance contributions planned for April. The truth is these figures make no difference to that calculation. Mr Sunak certainly could find money to delay tax rises or find other one-off ways of supporting living standards such as uprating benefits in April with a more up-to-date measure of inflation. But the long-run pressures on public services, especially health and social care, remain just the same and tax rises are likely to be needed if these are to be met. If he acts now on the cost of living, Mr Sunak will also need to find a credible means of committing to taking tough action on the public finances in the not too distant future.”

Even if the deficit does come in below the official forecast of £183bn, it will still be at a much higher level than that expected before the pandemic, when the forecast deficits for 2019/20, 2020/21 and 2021/22 were £47bn, £55bn and £67bn respectively compared with the much larger numbers reported in our chart. A variance of £13bn is also relatively small in the context of the £547bn increase in public sector net debt between March 2020 and December 2021.

All this suggests that the next fiscal event scheduled for 23 March 2022 is likely to take on even more importance as the Chancellor seeks to navigate between the rock of fiscal responsibility and a hard place of a cost of living crisis.