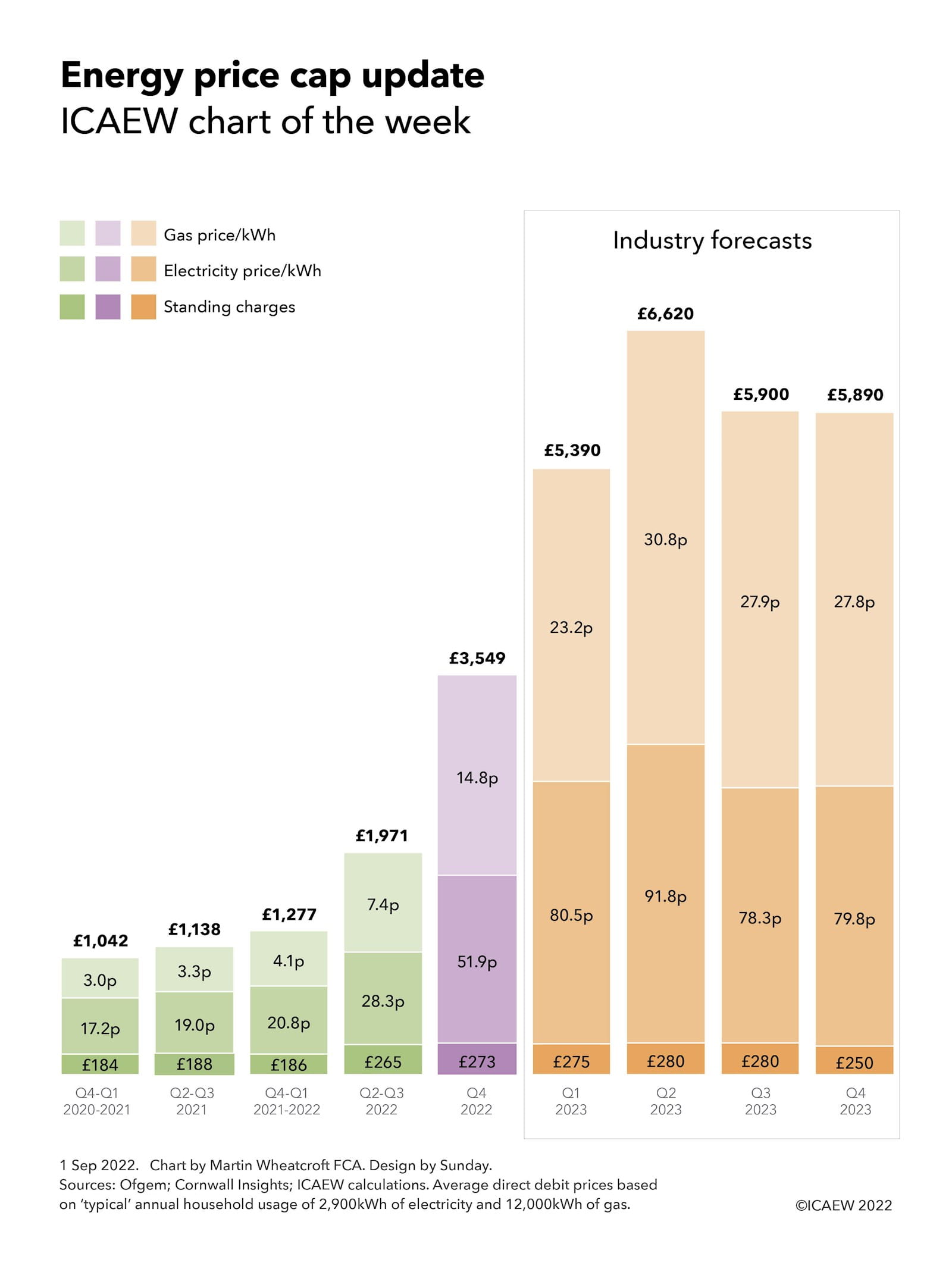

Our chart this week is on Ofgem’s cap on domestic electricity and gas prices, which increased from an annual average of £1,042 back in October 2020 for a ‘typical’ household using 2,900kWh of electricity and 12,000kWh of gas paying by direct debit, to £1,138 in April 2021, £1,277 in October 2021 and £1,971 in April this year.

Unless the new prime minister intervenes, the energy price cap will rise to £3,549 on 1 October, significantly more than was anticipated in our chart back in January on this topic . Divided by 12, this gives a monthly average bill of £296 (compared with £164 currently and £106 last winter), although as energy usage in winter is higher for most households the £400 or £66 per month rebate between October 2022 and April 2023 announced by the government earlier this year will not go very far.

The change to quarterly price caps from 2023 onwards means that households face a further rise in January, making the winter even more expensive given that research from Cornwall Insight suggests energy prices will continue to rise, to a likely cap of in the region of £5,390 on 1 January 2023 and potentially to as much as £6,620 on 1 April 2023, before falling to £5,900 on 1 July and £5,890 on 1 October 2023.

The energy price cap is technically a series of regional caps on the price per kilowatt-hour (kWh) for electricity and gas, and on the daily standing charge payable by domestic users. Larger or less energy-efficient households using more electricity or gas will pay a lot more than the amounts shown here, while smaller and more energy-efficient households will pay less. There are higher prices for those using prepayment meters (£3,608 from 1 October) and those paying by cash or cheque (£3,764 from 1 October).

The chart illustrates how the average annual standing charge was £184 in Q4 2020 and Q1 2021, £188 in Q2 and Q3 2021, £186 in Q4 2021 and Q1 2022 and £265 in the current price cap, the large increase principally to cover the costs of dealing with the 40 or so energy suppliers that went bust over the past year. The average standing charge will increase to £273 in October and then is expected to stabilise at around that level, potentially at £275, £280, £280, and £250 respectively for the four quarters in 2023, although this depends on how Ofgem chooses to allocate the costs that make up the cap between fixed and variable elements in the pricing structure.

The average per kWh price for electricity has increased from 17.2p (Oct 2020-Mar 2021) to 19.0p (Apr-Sep 2021) to 20.8p (Oct 2021-Mar 2020) to 28.3p currently and will rise to 51.9p in October. If Cornwall Insight’s predictions come to fruition, the price is likely to rise to somewhere around 80.5p per kWh in January and potentially to 91.8p in April, before falling to 78.3p in July and rising slightly to 79.8p in October 2023. The potential peak of 91.8p is more than five times the level back in October 2020 and is likely to be an even higher multiple for the many households who were on fixed price deals that were often significantly below the level of the price cap.

The average per kWh price for gas has increased from 3.0p (Oct 2020-Mar 2021) to 3.3p (Apr-Sep 2021) to 4.1p (Oct 2021-Mar 2020) to 7.4p currently and will rise to 14.8p in October. The gas price is likely to rise to 23.2p per kWh in January and potentially to 30.8p in April, followed by 27.9p and 27.8p in the final two quarters of 2023. The possible peak of 30.8p would be more than 10 times the level of 3.0p back in October 2020.

The price cap about to come into force of £3,549 is based on annually equivalent wholesale energy costs of £2,491, network costs of £372, operating costs of £214, social and environmental contributions of £152, other costs of £88 and a profit margin of £63, before adding on £169 of VAT at a rate of 5%. These are equivalent to £208, £31, £18, £13, £7, £5, and £14 in a ‘typical’ bill of £296 per month.

The sheer scale of these price rises will make energy unaffordable for millions of families across the UK at the same time as many other prices are rising sharply. This will mean real hardship for those on low and middle incomes without significant additional financial support from government, whether in the form of extra rebates on energy price rises or support through the benefit system. Other options include reforming the pricing mechanism for electricity generated by non-gas sources such as renewables or providing the energy suppliers with a long-term borrowing facility to enable the expected price rises to be spread out over a number of years.

Either way, the incoming prime minister faces some very difficult choices in how to respond, not only to the cost-of-living crisis but also to an emerging cost-of-doing-business crisis that could see many businesses forced to close as their energy prices (not covered by the domestic price cap) become unsustainable.

In January, we said: “There may be trouble ahead.” Unfortunately for all of us, trouble has arrived.

Readers can also visit ICAEW’s Inflation hub for a closer look at the impact of inflation on people, businesses, accountancy and the wider economy.

Join ICAEW's Energy & Natural Resources Community

Tailored content and networking opportunities for accounting and finance professionals in the energy sector, to help you stay up to date with the latest news and developments.