With professional judgement and ethics in the audit and accountancy profession in the spotlight in recent years, regulators, governments, professional bodies and firms themselves have been looking at ways to boost standards.

The importance of professional judgement and scepticism is being pushed for auditors, particularly in areas such as material fraud. In an environment where social and environmental impacts are becoming as important as profitability, the profession is looking at how it adapts.

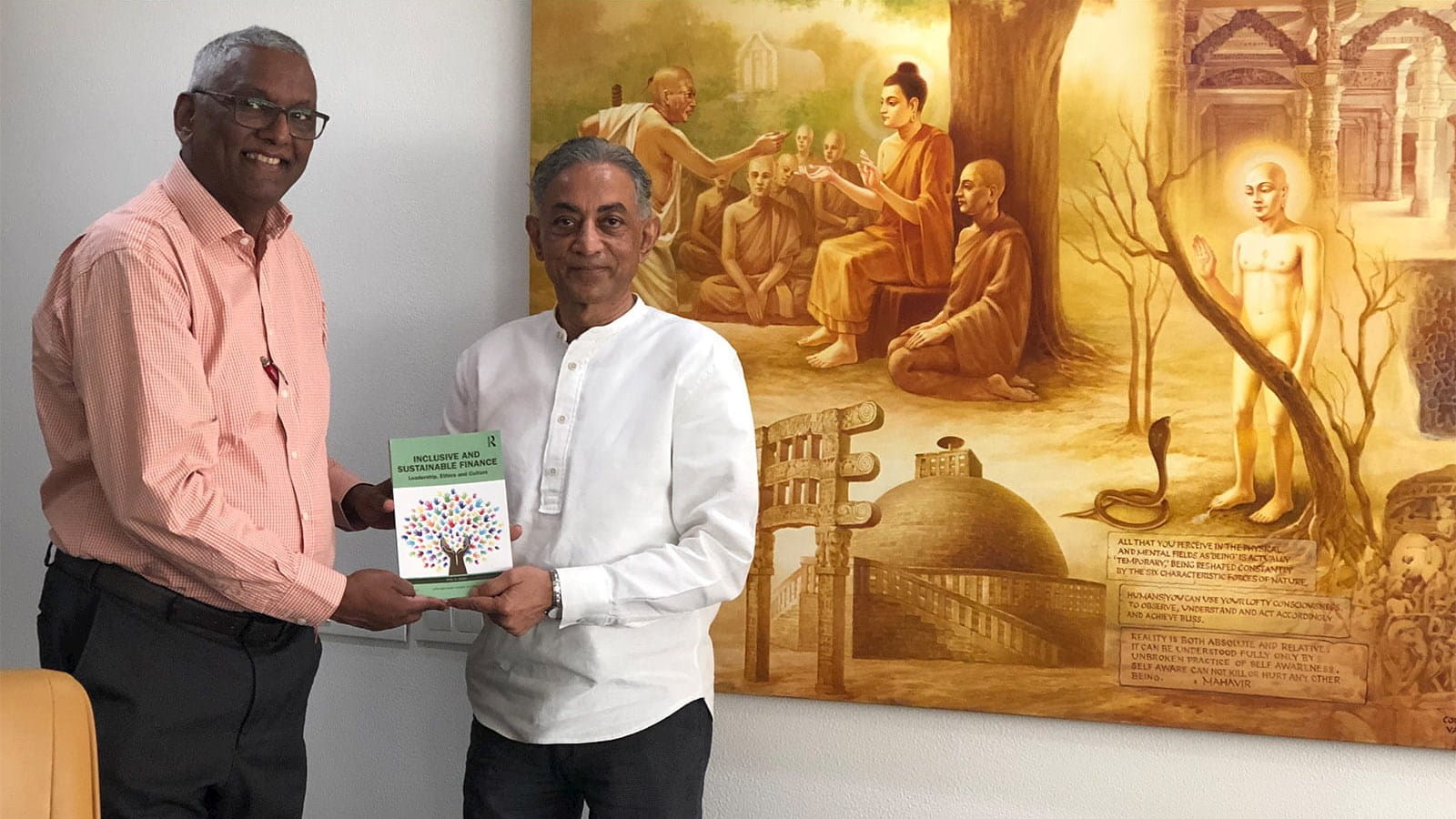

Professor Atul K Shah, Visiting Lecturer on Finance and Accountancy in the School of Policy and Global Affairs at City, University of London, believes in order to go forward, the profession must to an extent look backwards. His research for his book, ‘Inclusive and Sustainable Finance’, suggests that traditions, personal culture and beliefs should inform the ethical direction of an inclusive profession.

“Faith was critical to the early building of the profession, because it provided a bank of trust and goodwill,” says Shah. “In a way, the profession was effectively given a licence of trust because of the faith that was inbuilt in society at that time. Over time, we have come to diminish its importance and relevance.”

Shah believes that the right approach is inclusive, multi-faith and multi-belief. As part of his work, he interviewed professionals from Jewish, Christian, Islamic, Hindu, Jain, Yoruba, Sikh and Buddhist backgrounds, among others, to determine how personal beliefs can influence your professional judgement.

“The planetary crisis demands a huge ethical revolution, but the mindset won’t change, the structure of institutions won’t change, and the political system won’t change. We have no choice but to look at cultures and traditions that have survived the test of time and have promoted ethical business and finance,” says Shah. “My research shows that many of these cultures and traditions are alive and vibrant, and still practise sustainable values in finance.”

Shah believes that ethics is often taught to accountancy and finance students in a fairly transactional way. It doesn’t delve deeply into the role of conscience, reputation and honour, he says. “The public interest side of things often gets forgotten as a result.”

Accounting firms must encourage their employees to apply their personal belief systems and morals to their decision making within the organisation, Shah says, if they want to improve professional ethics and judgement. Shah, himself a Jain, uses Jainism as an example of how this could work.

“Among the Jains, we have something like 2.4 accountants per family, so there is something about the tradition, the culture and the mindset that makes Jains natural accountants,” he says. “I’ve spoken to clients of many of these accountants, and they are overjoyed with the quality of service – particularly when it comes to trustworthiness.”

Faith and tradition can provide a backdrop against which to raise issues of public interest, he explains. He points to another example: PwC’s Diwali party; the 300-400 people who attended have been highly praised by senior partners and the Head of People. “Where do those qualities come from? They come from the tradition, the upbringing, the culture. That is what they’re bringing to the firm.

“These are natural leaders. Let’s work with them – let's even work under them – to help us navigate the challenges that we're all facing.”

Firms and professional bodies need to encourage cultural conversations within the profession to encourage a stronger link between personal culture and finance, and for people to take on leadership roles within the profession with their personal morals at the centre of their decision making.“Otherwise, public interest will be just another exam to pass without any personal relation with protecting the welfare of others,” says Shah.

It’s about breaking the instinct for people to ‘smooth out’ their own beliefs in order to fit in within an organisation, which is easier said than done. It could produce some difficult conversations as a result, as people come to terms with where their belief systems cross over and where they differ.

“That’s a really difficult problem, but at the same time, ignoring It won’t make it go away,” says Shah. “Organisations have to find ways of opening the dialogue. There is a Venn diagram between culture, religion, belief and character. You can’t have a good culture in the workplace and leave your beliefs at home. When it comes to discomfort, we feel it every day at some point or another. It’s something that you can get used to.”

Shah himself is no stranger to discomfort, having taken a long route to feeling confident enough to share his views on ethics, tradition and belief. “It’s taken me three decades to feel confident about my own culture and my worldview. Now I feel this is my opportunity to make change at a time when it is necessary. We’re in an existential crisis at the moment, where we need to change the way that business operates to be more in harmony with the natural world, so the timing couldn’t be better.”

Professor Atul K Shah is launching ‘Inclusive and Sustainable Finance in India’ at Flame, Jindal and Ahmedabad Universities. He recently completed a TV interview for the Economic Times channel.

Join ICAEW's Internal Audit Community

Our new Internal Audit Community provides essential resources, support and news on the latest technical and regulatory changes impacting the internal audit function. Membership is open to everyone, including non-ICAEW members.