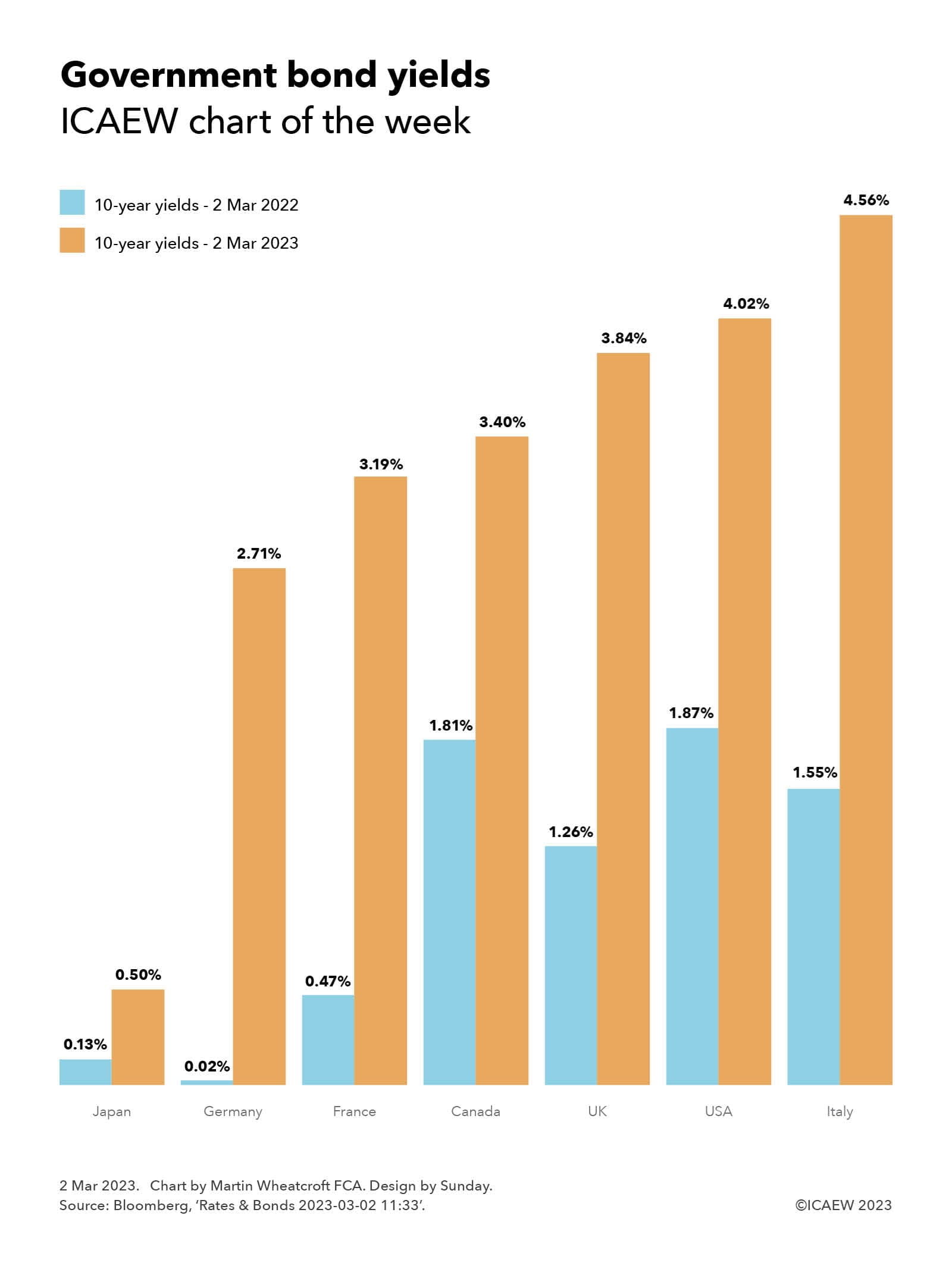

The past year has seen a dramatic change in economic fundamentals around the world as inflation has surged and growth has stuttered. One of the most dramatic changes has been to the cost of new government borrowing, with the yields payable by governments to sovereign debt investors increasing significantly from where they were a year ago.

As our chart of the week illustrates, Japan has seen yields on 10-year government bonds increase from 0.13% on 2 Mar 2023 to 0.50% on 2 Mar 2023, a far cry from the negative yields it has obtained over much of the last decade when (in effect) investors were paying the government of Japan for the privilege of lending it money. The change for Germany has been even more marked, from a position a year ago where it could borrow over 10 years for almost nothing (0.02%) to today where if it wanted to raise new funds it would pay an interest rate of 2.71% over 10 years.

The other members of the G7 have also seen the effective interest rate payable on 10-year government bonds rise, with France going from 0.47% a year ago to 3.19% today, Canada from 1.81% to 3.40%, the UK from 1.26% to 3.84%, the USA from 1.87% to 4.02%, and Italy from 1.55% to 4.56%.

Yields from 10-year government bonds are seen as a benchmark rate for most countries, as although governments can and do borrow for much longer periods – with market data often available for 20-year and 30-year bonds as well – most countries have average maturities of much shorter periods. The UK is an outlier in this respect with an average debt maturity on government securities of just over 15 years (before taking account of quantitative easing), in contrast with the more typical average maturity of seven years for Italian government debt.

Although the amount payable on new debt has risen significantly, this should in theory feed in to overall cost of government borrowing gradually as it will take time for existing government bonds to mature and be refinanced. For some time to come the overall cost of borrowing will continue to benefit from medium- and long-term government bonds that were issued at the ultra-low borrowing rates experienced over the last decade or so.

However, in practice not all government borrowing is at fixed rates, with many governments (including the UK) issuing inflation-linked debt, adding to their interest costs as inflation has surged. In addition, some government debt is short term or pays a variable rate of interest, while quantitative easing has seen central banks swap a substantial proportion of fixed-rate government bonds into variable-rate central bank deposits, increasing governments’ exposure to changes in short-term interest rates.

Either way, the rapid rise in the interest rates payable on sovereign debt marks a significant shift in the fiscal calculus for most governments when combined with much higher levels of debt in most developed countries. Lots more pounds, euros, dollars and yen will need to be diverted to servicing debt, making for hard choices for finance ministers as they work out their budgets for coming years.