Our chart this week celebrates the 50th anniversary of the introduction in the UK of Value Added Tax (VAT), the indirect tax on commercial transactions that now generates around 20% of tax receipts.

One of the big mysteries in the tax system is why so many small businesses and sole traders cluster just below the VAT threshold of £85,000.

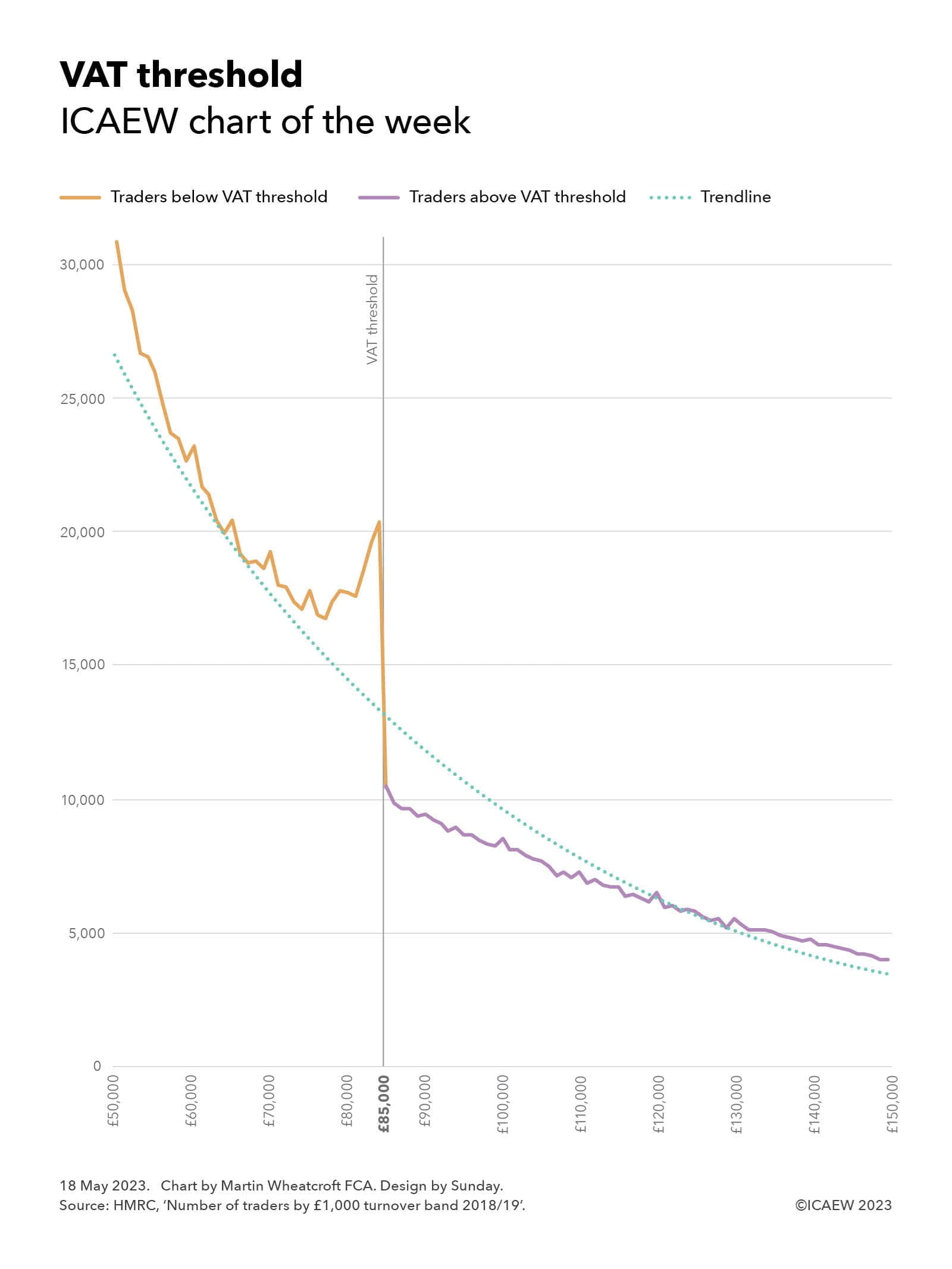

As illustrated by our chart, the number of businesses below the threshold gradually falls from almost 31,000 in the turnover band between £50,000 and £50,999 to just under 17,000 in the turnover band between £77,000 and £77,999, before diverging above the trendline to increase up to just over 20,000 in the £84,000 to £84,999 turnover band – immediately below the threshold for registering for VAT. This is almost twice as many as the just over 10,000 traders in the £85,000 to £85,999 turnover band, the first band legally required to register for VAT.

One explanation may be that there is some gaming (or possibly even misreporting) going on, with business owners approaching the threshold for VAT deciding to spread their business activities across multiple legal entities or keeping ‘cash-in-hand’ transactions off the books to avoid, or evade, adding VAT of 20% in most cases onto their prices.

However, perhaps a more worrying concern is if these businesses are not getting around the rules, but instead deliberately choosing to keep their businesses small given the competitive disadvantage that goes with adding VAT to prices charged to consumers, and the hassles and hazards involved with becoming a tax collector on behalf of the government.

This is a big issue for a UK economy experiencing weak economic growth. Not only is government income at stake, but also the wider benefits of more prosperous small businesses to the overall economy and what that means for the national economy.

Of course, many businesses do register despite being below the threshold, with around 1.1m traders in 2018/19 with turnover less than £85,000 signed up to VAT.

Other countries take a different approach, with much lower registration thresholds across most of Europe. Domestic thresholds range from nil in Spain, Italy and Greece, NOK40,000 (approximately £3,000) in Norway, €22,000 (£19,000) in Germany and €37,500 (£33,000) in Ireland, up to €50,000 (£43,000) in Slovenia. Switzerland is an exception with a higher registration threshold than the UK at CHF100,000 (£89,000).

In general, this means that a much greater proportion of actively trading businesses across Europe are registered for VAT compared with the UK, where there are estimated to be more than 3m or so traders with annual revenue of between £10,000 and £84,999 who have not registered for VAT – more than £100bn in total revenue.

Some believe that raising the threshold would provide a boost to the economy, given that many businesses would be more willing to grow (or declare) more of their revenue, while others believe the better option would be to reduce the threshold to capture many more businesses. The former would likely result in lower tax receipts overall, by allowing businesses just above the existing threshold to stop collecting VAT. The latter should in theory generate much more in tax receipts, perhaps as much as £20bn a year, in addition to removing one of the distortions that the tax system creates in this part of the economy.

The irony is that a relatively high VAT threshold in the UK designed to encourage and support small businesses may be one of the factors holding back economic growth. And with an unchanged threshold combined with inflation of more than 10% over the past year, this may be an even bigger drag on the economy/incentive to cheat than it has been in the past.

Click here to find out more about VAT at 50, ICAEW’s celebration (if that is the right word) of the 50th anniversary of VAT, and what the future holds for our most beloved of indirect taxes.