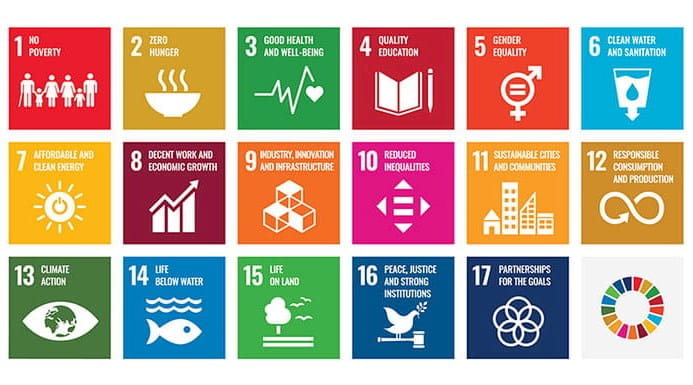

The defining principle for the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) was to leave no one behind when aiming to create a healthy, thriving planet. We’re now halfway towards that 2030 target date set out in 2015 and, as the threat of the climate crisis becomes more immediate, progress has slowed in many areas.

“The Sustainable Development Goals are disappearing in the rear-view mirror – as is the hope and rights of current and future generations,” states a recent UN report into SDG progress. “A fundamental shift is needed – in commitment, solidarity, financing and action – to put the world on a better path. And it is needed now.”

The UN’s preliminary assessment of around 140 targets for which trend data is available shows that only 12% are on track. Close to half of those targets, though showing some progress, are moderately or severely off track. Around 30% have either seen no movement or regressed below the 2015 baseline.

“Shockingly, the world is back at hunger levels not seen since 2005 – and food prices remain higher in more countries than in the period 2015-2019,” says the report. “The way things are going, it will take 286 years to close gender gaps in legal protection and remove discriminatory laws. And in the area of education, the impacts of years of underinvestment and learning losses are such that by 2030, some 84 million children will be out of school and 300 million children or young people who attend school will leave unable to read and write.”

Much of this falling momentum may be due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, says Jeremy Nicholls, Assurance Framework Lead for the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Capitals Coalition Ambassador and former Chief Executive of Social Value UK. However, some were already destined to be well off target.

One of the issues with the SDGs is that they did not include financial goals, he explains. But financial markets do influence progress on the SDGs and, unfortunately, the way that resources are allocated to investments is having a negative impact on climate and inequality. These negative impacts are occurring at a far faster rate than any positive steps.

“The figures around inequality over the last 20 to 30 years are mind-boggling, the extent to which wealth has become concentrated,” says Nicholls. “When you then also look at the climate effects over the last 30 years, it’s pretty scary. Unintended consequences of capital markets are busily driving us to the precipice faster than we are rowing backwards from it.”

Changing the way financial markets operate so they contribute to sustainability is easier said than done. They are, obviously, driven by financial returns, and to shift their focus to encompass broader sustainability performance would require a huge change: “It’s not set up to do it. Even if it was set up to do it, it would be quite challenging to change at the necessary rate.”

To put it another way, we’re quite used to living in an economy where businesses fail due to poor financial performance, but not one where businesses fail because of poor sustainability performance. This would require a fundamental change to global economic systems. But a transition like that would cause some businesses to incur significant financial losses and fail at a faster rate than new ones, aligned with sustainability goals, could replace them.

“New businesses would arrive with a rounder set of goals. All of our creativity and entrepreneurialism would be realigned,” says Nicholls. “I still remain optimistic that if you created that kind of global KPI, human creativity could achieve that. But the rate of progress we currently need requires a bit more subtlety around transition, I think.”

The political will also seems to be lacking when it comes to communicating the extent of the issue and what needs to change in democratic societies around the world, says Nicholls. Not enough politicians are talking about policies that will help us to transition in the fastest and fairest way. In the global north, while we’re feeling the consequences of climate change, it doesn’t seem urgent enough for significant action, he says. But it is already having devastating consequences in other parts of the world.

However, there are solutions. One is to review financial accounting standards and really scrutinise whether they are meeting the needs of today’s world. “The basic ideas were conceived alongside the development of universities, banking and during colonisation, but only became formal standards in the 1970s,” says Nicholls. “They have never really been challenged [and neither has] the risk that the way accounting standards calculate profit is driving these problems faster than we’re sorting them.”

Current standards for accounting for profits allow people to book profits without accounting for costs to other people, Nicholls explains. Even more bizarrely, they do not account for the costs to the business itself – and its people – through the effects of climate change. The fundamentals are never debated. One of the problems with non-financial reporting, he says, is that it leaves mainstream financial reporting in a separate box: “We need to see more done to align financial accounting standards with our sustainability goals. These costs are what economists call externalities – but they are only external because of the way accounting standards work.”

There has, however, been more progress in the legal and management spheres. More direct legal action is being taken by communities affected by the actions of organisations around the world. This is setting a precedent that will force businesses to be more accountable for the consequences of their activities.

Non-financial reporting standards are also improving and requirements on larger organisations now put their activities in a greater spotlight. While we don’t yet have a profit and loss equivalent for environmental and social impacts, there is movement in this area. “The Capitals Coalition members are doing a lot more to generate that kind of information. The UNDP standards that I work on basically state that you have to have it. I’ve argued that the International Sustainability Standards Board standard, whether it was specifically intended or not, talks about those issues in a way that could be interpreted as meaning that we need an impact profit and loss account.”

If that was put in place, there would be a much bigger shift in behaviours and actions, and things are moving in that direction. Similarly, operational decision-making in many organisations is taking SDGs into account. Internal controls and internal audit are looking at management systems that factor in SDGs. “The UNDP standards, I think, have a great basis for having conversations around those links between financial performance and sustainable impacts.”

There is also an increasing focus on the importance of audit in the assurance of sustainability information. “Audit is a fundamental public good. We simply would not have had public markets at the scale we do if there had not been an audit process that acted in the interest of investors. If we can get an equivalent sustainability audit, acting in the interests of the people experiencing the impacts, including climate change, then potentially we could drive standardisation around decision-making effectiveness at a much faster rate and unleash an equivalent contribution to sustainability and wellbeing.”

All this involves a great deal of change to shift progress towards where it needs to be, but that is the reality of the situation we find ourselves in, says Nicholls: “If we continue to live and work in our comfort zones, we’re probably not where we need to be.”

Latest Insights on UN SDGs

Open letter to the UK Government

On 18 September 2023 the world’s leading accountancy and finance bodies published a letter to the UK government urging transformative action to achieve the global SDGs and secure our collective future.