The three parties typically involved in an assurance engagement are: the responsible party, the users and the practitioner.

The responsible party performs operations or provides information for the benefit of or relevant to users. This party is responsible for the subject matter over which assurance is sought.

Users are typically the recipients of services, assets or information of the responsible party, although in some cases the relationship between users and a responsible party may not merely be one way.

The practitioner may be engaged to perform an assurance engagement in relation to the subject matter or the subject matter information that the responsible party is responsible for.

Either the responsible party or users, or in some circumstances both, may engage the practitioner. In all cases practitioner independence needs to be assessed and demonstrated.

The responsible party

The responsible party is responsible for the subject matter and subject matter information where produced.

Where there are two organisations (such as an assurance engagement assigned by a service provider), the responsible party typically performs operations or provides information for users in a manner usually governed by a written contract. However, the relationship between the responsible party and users is not always contractual or clearly defined.

Users

Users are the parties that are affected by the activities of the responsible party. In a business context, users may be in a contractual relationship with the responsible party to perform specific activities for their benefit. Where appropriate, users may also receive information in relation to the operations of the responsible party.

The type of the operation performed or information provided by the responsible party, the number of users, how they want the information reported the criteria used will vary. An assurance engagement may be performed in relation to all users or may be restricted to specific users. Where an assurance report is intended for specific users, the assurance report clearly indicates that fact.

In some cases, there may be users that are unidentified at the start of the engagement. This may happen where, for example, the responsible party intends to publish the assurance report on its website.

Where this is the case, the risk of the assurance report being received by those who are not party to the engagement, and therefore not fully appreciating what the report is for, may increase. The practitioner’s duty of care therefore needs be clearly reflected in the engagement letter, in the assurance report and throughout the conduct of the engagement.

The practitioner

The practitioner agrees with the engaging party the scope of the engagement, the reporting requirements and ensures that there is appropriate access to the personnel and information of the responsible party and, if applicable, external parties including the users.

The practitioner’s responsibilities will vary depending on who the engaging party is and their needs. To a degree, those responsibilities and needs will be driven by whether the engaging party is the responsible party, the users or both. The practitioner considers whether the responsibilities have been defined to an appropriate level including the nature of the deliverables when accepting an engagement.

In an assurance engagement, the practitioner is responsible for determining the nature, timing and extent of procedures so as to gather sufficient and appropriate evidence. He also pursues, to the extent possible, any matter of which he becomes aware and which leads him to question whether a material modification should be made by the responsible party to the subject matter information or to their assertions and to consider the effect on the assurance report if no modification is made.

Practitioner independence should be demonstrated through policies and practice which identify and evaluate circumstances and relationships that create threats to independence, with appropriate action to eliminate those threats or reduce them to an acceptable level, or, if considered appropriate, to withdraw from the engagement. This should involve establishing policies and procedures to reduce the familiarity threat to an acceptable level when using the same senior personnel on an assurance engagement over a long period of time.

Where practitioners are engaged to first carry out a readiness review, performing some testing and providing advice and recommendations, the scope of the readiness review should be carefully considered to avoid creating any self-review threat to independence in relation to a future assurance engagement.

For example, the practitioner will want to scope out any involvement in design and implementation of controls; and while the practitioner would reasonably expect to challenge and critique drafts of subject matter information, care would be needed to avoid straying into actual preparation.

Parties involved in an assurance engagement

The form of engagements may differ depending on which parties are involved in the assurance process.

Engagement with the responsible party

In engagements where the responsible party engages the practitioner, the practitioner performs an engagement to provide an assurance report over the subject matter (or subject matter information).

This will typically be with the objective of increasing the confidence of current users, or where so agreed prospective users, in the responsible party’s activities. The responsible party will often have contractual obligations to current users and may also be expected to comply with industry or other standards. It also has responsibilities to the practitioner in relation to the performance of the assurance engagement. (Read examples of these responsibilities and the potential consequences for practitioners.)

In this type of engagement, users may be identified or unidentified, existing or prospective, or combinations of these. Where users are unidentified, the practitioner accepts an assurance engagement only where a typical user is identifiable in the context of the engagement and the assurance report.

This is because, without a reasonably definable user or user group (such as ‘investors’), the practitioner may not be able to determine the suitability of the criteria against which to assess the subject matter or the subject matter information. The practitioner also considers the issues related to his duty of care.

Engagement with the users

There are other engagements where one or more users contracts with the practitioner to assess the operations of the responsible party, with the objective of increasing the users’ confidence over the activities of the responsible party.

In this type of engagement, the responsible party has contractual (or other) obligation to the users, and the users have responsibilities to the practitioner in relation to the assurance engagement.

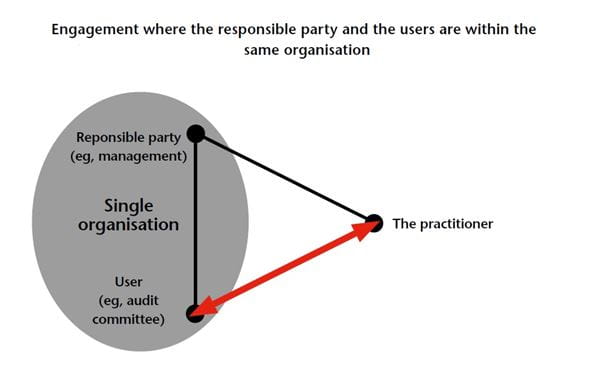

Engagement where the responsible party and the users are within the same organisation

While it is less usual for the responsible party and users to be from the same organisation, this situation can arise.In most cases, the responsible party or users anticipate or have in mind external users who would be interested in the subject matter, subject matter information, or relevant assurance reporting, regardless of whether an assurance report they commission would be made available to them or not. For example, annual reports contain a range of detailed disclosures.

Such disclosures are intended for shareholders and the statutory audit provides a degree of assurance over them. However, due to the relative sensitivity or importance of a specific aspect of disclosures, the audit committee may decide to obtain an assurance report on that aspect.

Such an assurance report may be issued to the audit committee, however, it is clearly requested with the interests of the body of shareholders in mind and the practitioner would bear the needs of the shareholders in mind when considering matters such as the criteria and materiality. The report would usually be addressed to the company.

In this type of assurance engagement, the practitioner needs to consider at the outset whether the engagement is feasible. The main risks involved may be that the client wishes to pass on the entire risk of misstatement to the practitioner; or it is only the users who are able to provide appropriate representations regarding the subject matter. For example, where only directors have the legal capacity to make representations on behalf of the company. Accordingly, the practitioner may appear to be bear the primary risk arising from a misstatement.

In such situations, especially in the case of direct reporting assurance engagements, it is important to understand the context of the (proposed) engagement and to establish whether, and if so how, these risks can be managed in different circumstances.

Examples of how such risks might be dealt with include:

ICAEW's assurance resource

This page is part of ICAEW’s online assurance resource, which replaces the Assurance Sourcebook.

Join the Audit & Assurance Faculty

Stay ahead of the rest with our comprehensive package of essential guidance and technical advice.

Buyer's guide to assurance on non-financial information

Find out more about the 'Buyer's guide to assurance on non-financial information' from WBCSD.

Find out more