While most charity boards are aiming to incorporate more service user perspectives in their governance structures, many charitable membership societies are relying on member perspectives alone. In this opinion piece, Baden-Fuller, Lawrey and Palmer explain why having independent trustees is a key element of good governance and adds depth to the skillset of the boards governing charitable professional membership societies.

Governance challenges

Charitable professional membership societies face unusual governance challenges because of the hidden and not so hidden tension between serving members and fulfilling the charitable purpose. The financial benefits of charitable registration are very significant: in the UK context it means that membership levies are not subject to corporation tax and fund raising can benefit from Gift Aid.

These governance challenges are not always clearly recognised, and even when recognised, often not properly addressed. A charity carries a legal obligation to work within the charity’s objects or purposes, and here membership societies are at risk because they often engage in activities that have a complexity of both private and social benefits, as the General Medical Council discovered to its cost*.

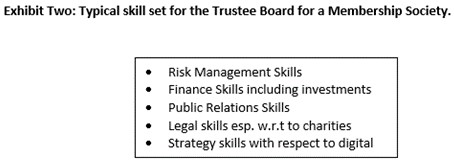

We argue that these challenges come to a single resolution, creating an effective Board of Trustees that is of modest size and that has an appropriate set of skills and expertise from within and without the membership. Such a Board of Trustees, as the governing body of the charity subject only to challenge by members in General Meeting has the responsibility for the legal, financial and overall governance dimensions of the society, and also for all its policy matters although detailed discussion may be left to various committees who may have more ability to decide the critically important dimensions related to membership and all the complexities of the professional activities. Technically, such committees, by whatever name, recommend proposals to the Board. The Board may adopt or not any of the recommendations and may even delegate implementation of the recommendations. However, what the Board cannot do is to delegate responsibility for the results of such implementation because the trustees, in charity law, are jointly and severally liable for the results of their decisions – whether they realise that or not!

Powers of the membership

Members, while in membership, ‘own’ their society and it is their ‘democratic right’ to elect their governors and to challenge the decisions of those governors when they think appropriate. Such powers exist in their constitutional documents (such as their Royal Charter of incorporation or their memorandum and articles of association or their Charitable Incorporated Organisation constitution) which underpin the membership contract between the charity and its members. Our evidence is that, while trustees – elected by the members – must continue to be able to set standards and exercise discretion over the competency of their members, the societies would benefit from the addition of some independent persons on their governing bodies with skills and experiences to complement those who come from within – to act as critical friends and so assure the public that what the society does is objective and not tainted in any way by self-interest. Such independents will crucially not be members of the society – which guarantees their lack of any conflict of interest – and may be elected by the members in General Meeting or may be appointed by the already-elected trustees who will be in the best position to know the skills or experience not already represented on the Board.

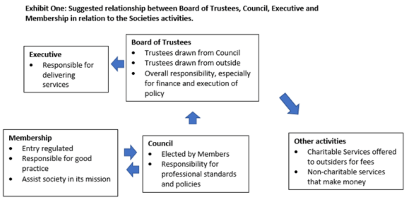

The ‘best practice’ relationship between these bodies, the Executive and the wider membership is illustrated in Exhibit One below.

There may be an intermediate body between the Board of Trustees and the sub-committees such as a Council (or Senate) which could be representative of the Membership, and which could include thought leaders of their profession. The Council (often large) works best through many smaller subcommittees that are engaged actively in the organisation’s professional work. The Board of Trustees should be a much smaller body, looking at wider issues such as finance, monitoring the Executive and professional staff, keeping and reviewing the risk register, and dealing with the Charity Commission and other regulators. The oversight Board of Trustees, being small and composed of both insiders and outsiders, has the ability to be agile and the capacity to deal with a wider set of governance issues that the society faces, including monitoring the executive and making sure that policies are executed effectively and within the social purpose.

Unfortunately, it seems that many charitable professional societies do not have these structures. Whilst they all have trustees, they do not always meet separately from the Council (or equivalent body), and even when they do, the structure of the board is not conducive to good governance. A survey we undertook of charitable professional membership societies revealed that less than half had independent trustees, and when they did, the numbers of independents was typically very small (see the report of the Foundation for Science and Technology, by Alana Cullen, 2020).

Recruiting independent trustees

Wise societies have appointment processes for trustees that are open, transparent, and allow proper scrutiny of the chosen outsiders.

In summary, getting the right governance for a charitable professional-membership society requires recruiting independent trustees with the correct skill set. They are an overlooked resource, to assist the membership achieve its mission.

Author email addresses: c.baden-fuller@city.ac.uk; profpalmer@city.ac.uk; keith.lawrey@foundation.org.uk

The views expressed are the authors’ and not ICAEW’s.*The UK courts decided that the General Medical Council (GMC) as originally constructed failed to meet the public benefit test. The GMC had to change its constitution and ways of working to achieve the right balance. As summarised in https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/general-medical-council, the reconstructed GMC emphasises the benefit to the public in training and the application of professional standards, in the GMC case for health professionals, with any personal benefits to individual medical practitioners or the medical profession being no more than incidental to achieving the charitable purposes.