With new US President Biden focusing on climate change, and businesses looking beyond the pandemic, many expect a new impetus for green investment. Katherine Steiner-Dicks looks to the next G7 Summit and the role Britain could play in the zero-carbon world

Amid all the events of 2020, one green landmark was passed on the march to a zero-carbon world. In the UK and EU, electricity generated from renewable sources overtook that from fossil fuels, according to research by thinktank Ember. And of course, across the pond, 2021 has started with a new US president. After four years of climate change rollbacks under the Trump administration, within hours of being sworn in, President Joe Biden had signed executive orders to rejoin the Paris climate agreement and put together the largest team ever in the White House to tackle global warming. It all points to a renewed vigour around green M&A and investment, as the world tries to look beyond COVID-19 too.

This should be a big green year for the UK. Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Chancellor Rishi Sunak have promised to make the City of London the global centre for green technology and finance. The next G7 Summit is due to be held in Cornwall, home of the Eden Project, in June. And the COP26 climate change conference in Glasgow is pencilled in for November, albeit a year later than originally planned.

Last year the UK put its net-zero carbon target into law. The focus to date has been on reducing emissions. This has in no small part been by importing goods and exporting emissions, says Gavin Quantock, a partner at KPMG and co-head of its specialist energy lead advisory team. “We need to do a lot more in the coming years to be more radical. If you look at the UK on a per capita basis, we are strong users of carbon.”

Sam Hollister, director of economics and corporate services at Energy UK, says the country needs to up its game. “The zero-carbon policy has to go from a nudge to a shove, stop being a nice-to-have and become an essential.”

Financing change

In November, Sunak made a pledge that Britain’s first green sovereign bond would be launched in 2021, to ‘build out a green curve’. The UK is behind Europe, China and the US on government-backed green financial instruments: Germany launched its first green government bonds in 2020, following Poland, France, the Netherlands and Ireland. The UK government will invest £12bn in the bonds, and the private sector is expected to provide three times that amount. Issuers want certainty in a post-Brexit marketplace, more than the prime minister’s words. Crucially, investors will need to be sure they are backing assets that will achieve zero-carbon goals on budget and on time.

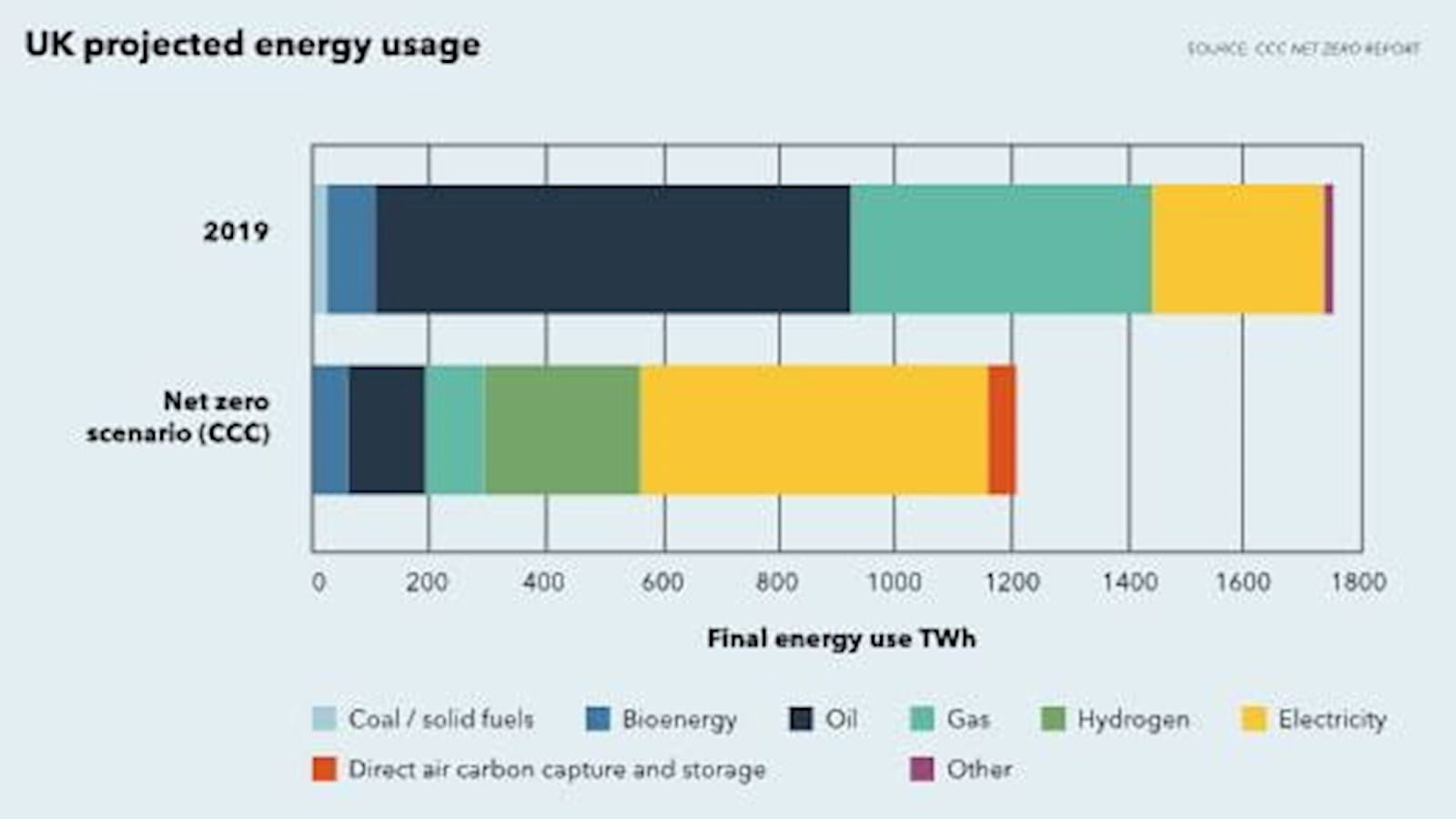

The UK’s Climate Change Committee (CCC; the independent statutory body established under the Climate Change Act 2008) has already signalled that the 2020s must be a “decisive decade of progress and action” on the issue. By the early 2030s, every new car and van and every replacement boiler, and by 2035, all UK electricity production, must be zero carbon. The Prime Minister’s Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution is ambitious. Decarbonising 28 million UK homes will likely prove the biggest challenge.

Energy UK’s Hollister says the UK’s net-zero green agenda represents a ‘seismic change, in no small part because it is legally binding’. He adds: “The challenges really lie in raising the amount of investment for clean electrification, expanding the power grid to four times the size it is today, and absorbing and sharing those costs. Then there is the huge challenge of a much more renewable-based system, including, for example, seasonal storage or greater flexibility for when the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow. The radical issues to solve are going to be in heat and transport.”

So too is mindset. British CEOs’ understanding of the implications is poor, according to a BSI survey – 64% were not confident they fully understood the impact of zero-carbon policies on their business, while 82% said they needed more guidance. Persuading business that the government is serious will be a task too. News that the UK’s new business secretary, Kwasi Kwarteng, accepted substantial donations from fossil fuel investors as part of his 2019 general election campaign does not help.

World’s a green stage

Globally, governments, companies and households invested $303.5bn in new renewable energy capacity in 2020, up 2% on the year before, helped by the biggest-ever growth in solar projects and a $50bn increase for offshore wind, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF). They also spent $139bn on electric vehicles (EVs) and associated charging infrastructure, up 28% to a new record.

Europe (including the UK) accounted for the biggest slice of global energy transition investment, at $166.2bn (up 67%), with China at $134.8bn (down 12%) and the US at $85.3bn (down 11%). It was a record year for electric vehicle sales, and Tesla founder Elon Musk’s net worth grew to $185bn.

Carl Swansbury, a partner and head of corporate finance at Newcastle-based advisory firm Ryecroft Glenton Corporate Finance, says: “The emission targets and consumer tax reliefs have created the EV market; without them I doubt the market would exist. Businesses like Tesla have identified government policies and built a business on the back of it.”

But how much will the transition from fossil fuel to zero-carbon emissions cost? According to the BNEF report, between $78trn and $130trn of new investment is needed by 2050 – $64trn on power generation and the electricity grid, and between $14trn and $66trn on hydrogen manufacturing, transport and storage. The world’s largest EV market, China, will be critical to the growth of EV-related companies.

One of the largest retail energy deals to close in 2020 was UK-based clean energy retailer Octopus Energy’s $250m partnership with Tokyo Gas. Octopus is now worth $2.1bn. Its sister company, Octopus Renewables, funds solar panel sites, wind generation and anaerobic digestion. Its solar farms make up 40% of the large-scale solar generation in the UK.

KPMG acted as lead advisers on the transaction. “Japan lags behind the UK with only 18.9% of electricity generated by renewables compared with 37.9% in Great Britain and Northern Ireland,” says Quantock. “With leaders in Japan and across Asia now fully embracing the shift away from traditional power sources, there’s a golden opportunity for a UK-founded company to be right at the heart of the renewables revolution.”

Purchasing power

Non-energy sector corporates are also driving deal flow through their venture arms and increasingly through clean energy purchase power agreements (PPAs).“We are seeing some corporates wanting to reduce their carbon by entering into long-term PPAs,” says Quantock.

The main drivers for this are the ESG agenda and, in some countries, green power now being cheaper than brown power. “They’re not just wanting to buy green power from existing renewable assets, they want to sign a PPA with a new wind farm or solar farm so they can say they have delivered additional green generation in the UK and the EU. It’s enlightening – they want to own their own clean energy assets. Very strong and record-setting multiples are being observed for subsidy-free onshore assets. I would say values and deal activity are strong across all areas of green investment.”

Corporate giants continue to drive the flow of clean energy deals. At the end of last year, Amazon signed the largest ever corporate procurement deal for renewable energy: 3.4GW from 26 projects across four continents. It is more than double the 1.6GW deal Google signed in September 2019. According to GreenBiz, more than 7.3GW of US corporate renewable procurement deals were signed in Q4 2020.

But what about fossil fuel companies? Last year, according to S&P Global analysts, Shell held back on renewable energy M&A. BP and Equinor formed an offshore wind joint venture, and Total acquired a 3.3GW portfolio of early-stage solar projects in Spain. BP CEO Bernard Looney said the push into renewables would be accelerated through joint ventures in solar as well as offshore wind projects. In January this year, Shell acquired Ubitricity, the UK’s largest public EV charging network.

“Corporate venture arms are all about trying to replace what will in time be significantly reduced revenue streams,” explains Swansbury. “While there has been a large amount of interest in renewable energy projects or clean tech from larger corporates like Shell and BP, most of the time the investment comes from private equity houses. The big corporates have onerous terms since they want greater control of all aspects of their business and supply chain. When a greentech business is looking to raise £10m of investment, will they be willing to sell a large piece of the business so early in development?”

At the end of last year, Swansbury advised on the MBO of Chameleon Technology, a £40m turnover smart energy business backed by London-based debt provider Shard Credit Partners. Swansbury says that, despite the best intentions, large fossil fuel corporates remain hesitant about investing in renewable assets, which over time risks diminishing their market position. “The supergreens will replace them. It can literally be like trying to turn an oil tanker.”

Cadent, National Grid Gas, Northern Gas Networks, SGN and Wales & West Utilities are working together to create the world’s first zero-carbon gas grid by speeding up the switch from natural gas to hydrogen for the 85% of UK households connected to the gas grid. They have even suggested the government’s 2030 hydrogen production target be doubled from 5GW to 10GW.

Hydrogen is being taken seriously worldwide. Hydrogen technologies will have huge export potential if the UK can take a lead. Luke Clark, director at RenewableUK, which is working on the government’s hydrogen strategy, says: “It is critical to develop the markets and demand signals that will make our renewable hydrogen ambitions a reality.”

The global green boom will inevitably be tied to the economic recovery from the pandemic. Each country will face its own challenges in meeting zero-carbon targets. In the UK, green electrification of businesses and homes is going to be the biggest challenge. Nations will need to work together on research, trade and technologies in line with the Paris Agreement to accelerate the long march to zero carbon. The global market for such tech and innovation will undoubtedly fuel increased M&A in the sector.

-

Sunlit Uplands

The Development Bank of Wales (DBW) manages the Welsh government-backed £12.5m evergreen Local Energy Fund. Solar energy co-operative Egni received a £2.12m loan from the fund, and has raised another £3m from community shares to finance the biggest roll-out of rooftop solar panels in Wales. It aims to install panels on 128 premises, including community buildings, businesses and schools. Participants are offered a 20% discount on electricity cost, and several small community sites have benefited from free solar-generated electricity.

“The social enterprise model for renewable energy projects has proved interesting,” says Rhian Elston, investment director at DBW. “You’ve got public money provided through a loan, which can be recycled to the next project. A social enterprise recycling profits into the community. And you’ve got local share ownership, along with zero carbon benefits.” However, the project is one of the last to benefit from the UK’s feed-in tariff. “The absence of feed-in-tariffs will leave a big gap. It remains to be seen how that will change the viability of projects like this,” adds Elston.

-

Community cares

In April 2015, the UK government put a stop to VCTs, EISs and SEISs being able to invest in renewable energy schemes. This spurred Albion Capital to raise the £105m Albion Community Power fund, with partner David Gudgin at the helm. That fund has now been fully invested in 50 renewable projects.

The fund delivered unlevered returns of 15-20% for shareholders, more than a third higher than the target. Two investors felt it was an opportune time to realise their investment. And last year Albion was able to raise £57m in long-term, non-recourse, institutional, RPI-linked debt from funds managed by Aberdeen Standard Investments to refinance the assets.

Albion has raised and deployed more than £250m in the UK renewables sector over the past decade. Gudgin sees a bright future in community-based projects: “One of the things that’s changed over the past five years is a willingness by the banks and institutions to finance where they weren’t previously. That is why we have been able to introduce debt into the fund.”

The portfolio is diversified across solar, wind, hydro and battery storage. “This not only balances out the intermittency, but balances returns for investors,” says Gudgin. Hydro accounts for 25% of the portfolio but, he adds, “Sadly, without a renewed feed-in tariff or some other subsidy, new hydro schemes have slowed to a trickle.”

The firm is also making hybrid clean energy investments in combined renewables and battery storage. Another driver is corporates taking a different approach to renewables, entering into long-term PPAs from new renewable assets rather than existing green assets. “They can then say that their new agreement has delivered additional green generation in the UK and the EU.”

-

Biden’s $2trn climate boost

Gina McCarthy, a former head of the Environmental Protection Agency, will be the US’s first climate tsar as new President Joe Biden sets his sights on climate change. This might be a breath of fresh air for environmentalists and green investment funds, but Biden will need to ensure it is not at the expense of unionised jobs. Renewables, climate and energy tech are at the heart of the US economic stimulus programme, which includes a $2trn climate policy.

The US has the massive task of building out renewable energy and energy storage to meet its net-zero carbon emissions target by 2050. The ambitious green agenda will be a welcome one following an 11% dip in energy transition investment to $85.3bn in 2020, due, in part, to COVID-19 pandemic delays. However, US companies invested $23bn in EV development last year, around the same as the industry typically invests in conventional vehicle development. Fossil fuels, however, still account for 60% of US generation, which means there is a lot to go after.

-

Looking outward

Until recently, the Chinese renewables and energy transition deal market had been pretty insular. But even China recognises that outside support might be needed when it comes to funding and technology transfer. Its government is promoting the energy industry in pilot free-trade zones such as Guangdong, Hubei, Chongqing and Huainan. It reported that the likes of ExxonMobil, GE, BP, EDF and Siemens are steadily expanding investment in China. Tesla’s Shanghai plant is well under way.

“China’s 2060 zero-carbon target is the most significant zero-carbon target in the world,” says Hannah Routh, Deloitte UK senior partner responsible for building the firm’s team to deliver climate change. Until last year Routh was based in China as head of its Asia Pacific climate change and sustainability advisory practice. “If China achieves this, it is estimated it would reduce climate change temperature increase by between 0.2-0.3 degrees Celsius. China has already shown it can develop, manufacture and deploy renewable energy and clean technologies at a scale unseen in any other country.”

To hit the 2060 target while continuing economic growth will require multiples of the current level of investment, including “significant investment in hard-to-decarbonise sectors and next-generation technologies like green hydrogen and energy storage,” says Routh. “Competition between China and the EU is expected to drive down prices, as it did for solar photovoltaic technologies a decade ago.”

Companies to watch include Chinese oil refiner Sinopec, which aims to become the largest supplier of hydrogen energy. It has formed an alliance with four of China’s largest solar energy companies to develop green hydrogen projects.

What is the opportunity for UK cleantech in China? “It is mutually beneficial for China and the UK. Positive results will also benefit the rest of the world. With the US re-joining the Paris Agreement, and the UK hosting COP26 this year, it is reasonable to expect a period of climate cooperation and technology transfer to tackle this urgent global problem.

More on corporate finance

ICAEW's Corporate Finance Faculty represents the interests of its members with policymakers and facilitates a highly effective business development network.