What is the deficit?

The fiscal deficit is a shortfall between the amounts raised by the government each year in tax and other receipts and the amount of public spending.

It is equal and opposite to public sector net borrowing (PSNB), being the amount that the government needs to borrow to cover the shortfall.

In the rare occasions that tax and other receipts exceed public spending, then the excess is a fiscal surplus that can be used to repay borrowing.

The fiscal deficit is not the same as public debt, which is the cumulative amount of borrowing built up over the years.

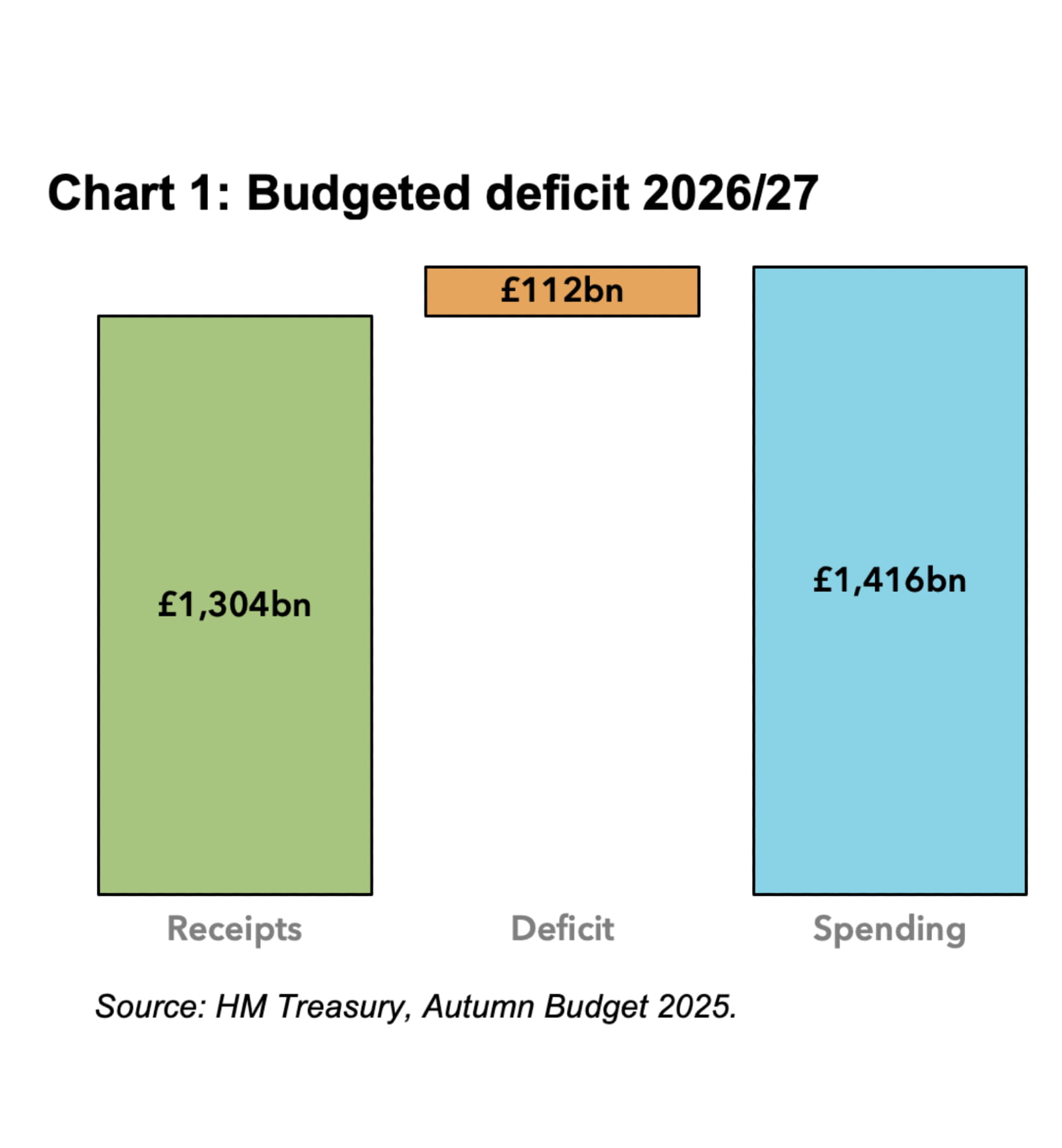

The government has budgeted for a deficit of £112bn in the financial year ending 31 March 2027 (2026/27), being the shortfall between expected tax and other receipts of £1,304bn and planned public spending of £1,416bn.

Public spending for this purpose includes capital investment in addition to operational or day-to-day expenditures.

What is the current budget deficit?

Public spending can be split between current, or day-to-day, spending and net-investment spending, with the difference between tax and other receipts and current spending known as the current budget deficit (or surplus).

Net investment comprises capital expenditure on assets and capital transfers (such as capital grants, irrecoverable student loans, and research and development expenditure) less depreciation charges on existing assets.

The current budget deficit or surplus tends to get less prominence that the overall fiscal deficit but as the basis for Chancellor Rachel Reeve’s primary fiscal rule it is increasingly important.

Table 1: Budget and fiscal rule target years

Receipts and expenditures |

2026/27 |

2029/30 |

|---|---|---|

Taxes and other receipts |

£1,304bn |

£1,483bn |

Current spending |

(£1,333bn) |

(£1,461bn) |

Current budget (deficit)/surplus |

(£29bn) |

£22bn |

Net investment |

(£83bn) |

(£90bn) |

Total deficit |

(£112bn) |

(£68bn) |

Table 1 shows how the Chancellor has budgeted for a current budget deficit in 2026/27 but is targeting a current budget surplus of £22bn in 2029/30, the fourth year of the fiscal forecast.

This targeted surplus provides ‘headroom’ as it is the amount by which the forecast for 2029/30 could deteriorate while remaining in compliance with the Chancellor’s primary fiscal rule (which is to be in surplus in the fourth year of the forecast period).

How does the deficit affect people and businesses?

Borrowing more to run a larger deficit in the current year allows the government to avoid putting up taxes in the short-term. The downside is that doing so adds to the total amount of debt, increasing the interest bill and weakening the public finances – leading to the prospect of higher taxes in the future if economic growth is not strong enough.

There is also the risk that too much borrowing could cause debt investors to take fright, as happened following the ‘mini-Budget’ in October 2022 when interest rates rose sharply, and financial markets were disrupted.

The challenges in controlling the deficit

Most developed countries choose to run a deficit. This is firstly because it makes sense to borrow to invest in infrastructure that will grow the economy, or in operational assets that will make the public sector more efficient.

Deficits also occur during economic crises such as the financial crisis, the pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis. These can cause receipts to fall and spending to rise at the same time, resulting in very large deficits.

Some countries, including the UK, also run deficits to fund current expenditures, deferring day-to-day costs onto future generations. This is often because it can be easier politically to borrow than it is to put up taxes.

Big challenges in controlling the deficit include:

- More people living longer, which is pushing up the costs of pensions, health and social care.

- Weak productivity which has resulted in low levels of economic growth since the financial crisis.

- The political difficulty in raising tax to fund spending.

- Planning and other constraints that make it difficult to invest in infrastructure that would generate economic growth.

- The deteriorating quality of public services and pressures to improve them.

- Interest rates that increase the cost of debt, squeezing other categories of spending.

- The end of the ‘peace dividend’ that means that it no longer possible to find money for pensions, health and social care by cutting the defence budget.

- Events, such as the financial crisis, the pandemic, the cost-of-living crisis or a major recession, that can cause receipts to fall and spending to rise at the same time.

What is the outlook for the deficit?

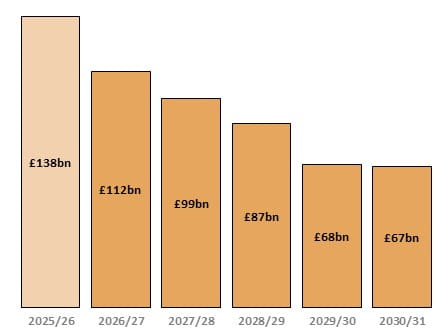

The current plan is to gradually reduce the deficit over the next five years, from an estimate £138bn or 4.5% of GDP in 2025/26 to a projected £67bn or 1.9% of GDP in the year ending 31 March 2031.

This hoped for reduction in the annual deficit – and hence in the amount the government will need to borrow to fund it – assumes the government can deliver a current budget surplus (ie taxes and other receipts in excess of day-to-day spending) of £25bn in 2030/31.

This will require the economy to grow sufficiently to provide the level of tax receipts needed and tight cost control and efficiency savings to keep public spending in line with plans.

ICAEW on the Budget