Financial reporting is the process of recognising, measuring and disclosing information that enables users to get an informed view of the financial position and performance of an entity that should allow them to make useful decisions and hold the entity to account. Business combinations such as acquisition and mergers play an important role in corporate as well as public sector environments but there are key differences.

Introduction

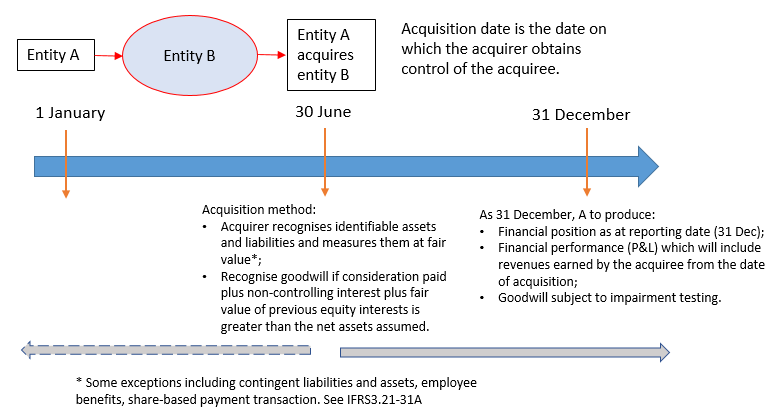

Acquisitions play an important role in the private sector and being able to evaluate the nature and financial effects of the business combination goes to the heart of the relevant financial reporting standard, IFRS 3 'Business Combinations'. This standard applies the acquisition method to account for the assets, liabilities and any non-controlling interest acquired in the business combination.

In developing IFRS 3, the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) concluded that 'true mergers' or 'mergers of equals' in which none of the combining entities obtains control of the others are so rare as to be virtually non-existent. Therefore IFRS 3 considers all business combinations to be acquisitions where the acquirer gains control of the business of the acquiree.

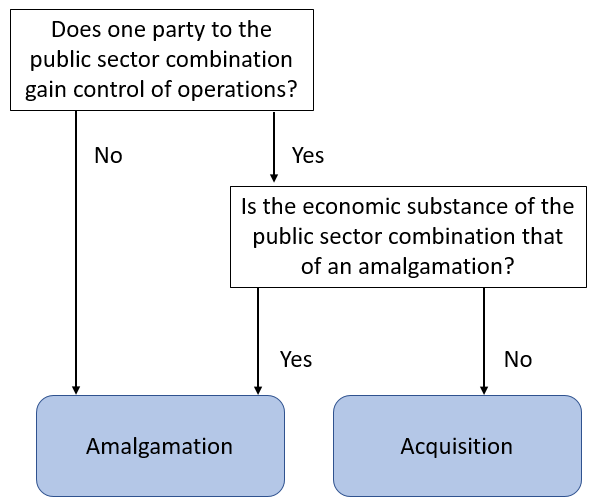

By contrast, IPSASB noted that many (but not all) public sector combinations are mergers or amalgamations. Amalgamations give rise to a resulting entity where no party gains control or if one party does, there is evidence that the economic substance is that of an amalgamation. As such, IPSAS 40 'Public Sector Combinations' provides guidance for both amalgamations and acquisitions. Amalgamations are accounted for using the modified pooling of interest method as per IPSAS 40 and specifically includes entities under common control.

Classifications – a brief history

In developing IPSAS 40, IPSASB initially considered developing two standards on public sector combinations based on exchange and non-exchange transactions with the former being an alignment project with IFRS 3. An exchange transaction is a transaction which involves the exchange of goods or services of approximately equal value. IPSASB did not proceed with this approach for a number of reasons, one being that based on the definition of exchange transactions, most government interventions during times of economic crisis, such as the global financial crisis in 2008, would not meet the definition of an acquisition. IPSASB considered it inappropriate to define such 'bailouts' as amalgamations. IPSASB changed their approach and decided to create one single standard that includes acquisitions and amalgamations. They considered that the concept of control was important to determine the classification of a public sector combination and believed this should form the basis upon which to distinguish acquisitions from amalgamations.

However, distinguishing acquisitions from amalgamations based solely on control met with some resistance as some stakeholders did not think it always reflected public sector circumstances. They argued that the acquirer may not always be identifiable since the entity gaining control of the operations may not have existed prior to the combination and that public sector combinations may be imposed on all parties to the combination by a higher level of government, which in turn renders control factors irrelevant.

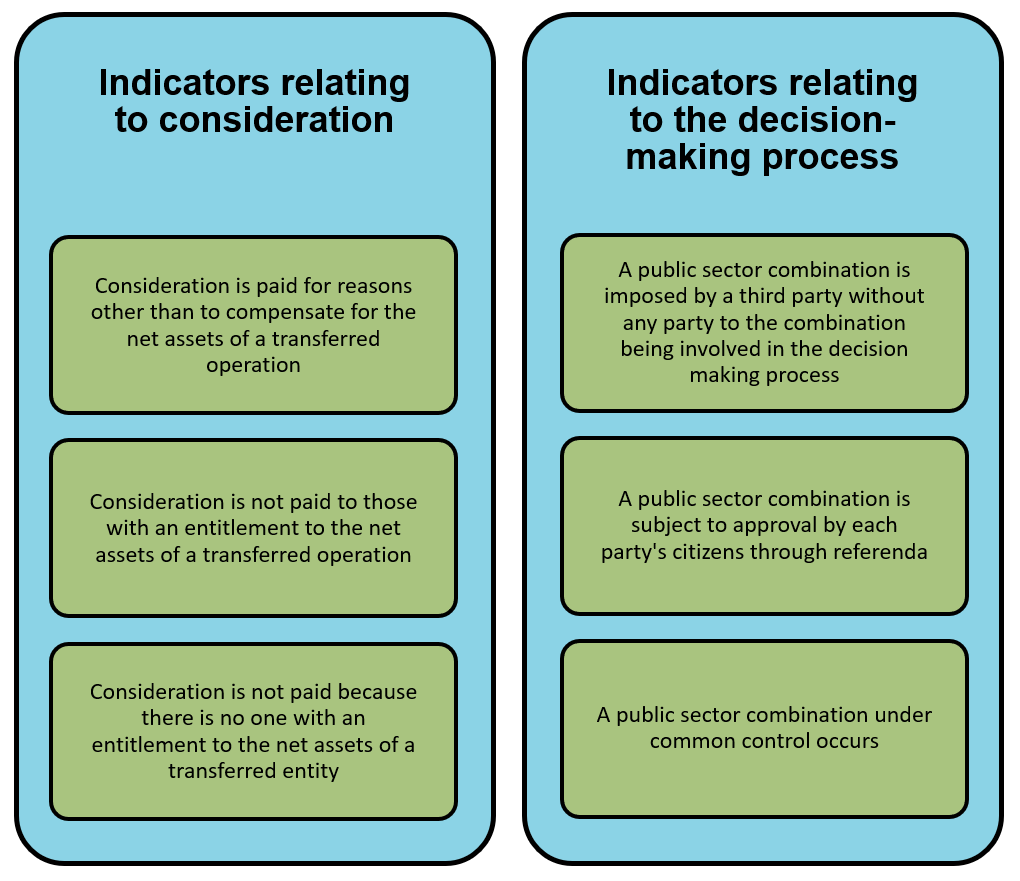

IPSASB discussed additional factors (consideration, exchange transactions, quantifiable ownership interests, decision-making process, compulsion, common control and citizens' rights) and concluded that control should be supplemented by two additional features – whether consideration was transferred, and the reasons for the presence or absence of consideration; and the decision-making process.

Control remains important, as its absence eliminates the possibility of an acquisition, but its significance in determining the economic substance of a particular combination where one party has gained control is a matter of professional judgment.

Amalgamations – the main difference between private and public sector

IPSAS 40 provides guidance for both acquisitions and amalgamations whereas IFRS 3 only covers acquisitions. So, what is the difference?

An acquisition results in one party to the combination gaining control of the acquiree’s business. An amalgamation is a public sector combination in which no party gains control of one or more operations or if one party does gain control, the substance of the combination is that of an amalgamation.

A key feature of IPSAS 40 is to differentiate between whether the combination is an acquisition or an amalgamation.

Classification approach:

To assess the economic substance of the combination, an entity considers the indicators relating to consideration and to the decision-making process (see below). These indicators, individually or in combination, will usually provide evidence that the economic substance of the combination is that of an amalgamation.

As the indicators relating to the decision-making process above show, when a public sector combination takes place between two parties that are under common control, this may provide evidence that the economic substance of the combination is that of an amalgamation. Entities that are under common control are entities controlled by the same entity both before and after the public sector combination.

Public sector combinations under common control are often instigated by and on behalf of the controlling entity, and the controlling entity will often determine the terms of the combination. For example, a government may decide to combine two ministries for administrative or political reasons and specify the terms of the combination. In such circumstances, the ultimate decision as to whether the combination takes place, and the terms of the combination, are determined by the controlling entity. This provides evidence that the economic substance of the combination is an amalgamation. [IPSAS 40, AG37]

The IASB, at the time of pronouncing IFRS 3 in 2004, concluded that 'true mergers' or 'mergers of equals' in which none of the combining entities obtains control of the others are so rare as to be virtually non-existent in the private sector. This decision is now being reviewed since stakeholders have fed back that the lack of a specifically applicable IFRS for business combinations under common control has resulted in diversity in practice. The IASB issued a discussion paper in November 2020 on possible reporting requirements that would reduce diversity in practice and provide users of the financial statements with better information about the combinations. The IASB continue to deliberate whether the project would justify the necessary resources - no decision was taken at the April 2023 board meeting.

How amalgamations are accounted for under IPSAS 40

Amalgamations are accounted for in IPSAS 40 by applying the modified pooling of interest method of accounting.

To illustrate the key principles of the modified pooling of interest method, the following example is taken from IPSAS 40.IE181.

Assume that municipal entity A and municipal entity B have been instructed to merge their activities – they are entities under common control and so this combination meets the classification of an amalgamation. They have a year end of 31 December, and the date of the amalgamation is 30 June.

Overview of amalgamation of entity A and B to form a new entity RE:

The entity that obtains control of the combining operations following an amalgamation (the resulting entity), shall recognise the identifiable assets, liabilities and any non-controlling interest that are already recognised in the financial statements of the combining operations as at the amalgamation date. All assets and liabilities shall retain their previous classifications and designations such as assets held at amortised cost or fair value. Any transactions between the combining operations are eliminated and removed.

The resulting entity shall measure the assets and liabilities at the same values as they were in the financial statements of the combining operations as at the amalgamation date. However, these values may be adjusted to conform to the resulting entity's accounting policies.

An amalgamation does not give rise to goodwill.

Unlike the acquisition method, the resulting entity shall recognise within net assets/equity amounts equal and opposite to the carrying value of the combining operations' assets, liabilities and non-controlling interests. These can be presented as a single opening balance or as separate components of net assets/equity. The example below shows the balances in the top half of the balance sheet being mirrored in separate components within net assets/equity.

In the example above, entity B did some work in May for entity A but the invoice of CU750 was outstanding at the amalgamation date of 30 June. This resulted in entity B recording a debtor balance against entity A and in turn entity A recorded a payable to entity B. These internal balances need to be removed and thus as per the table above, assets and liabilities are being reduced by CU750.

The financial statements of entity A and B also need to be adjusted for any differences in accounting policies that are adopted by the new entity RE. In this instance, the new entity adopts a revaluation model for property, plant and equipment (PPE), whereas entity A applies the historic cost model. In this case the revalued amount of PPE for entity A is increased by CU5,750 with the corresponding entry going to the revaluation reserve in net assets/equity.

Brief overview of acquisition accounting

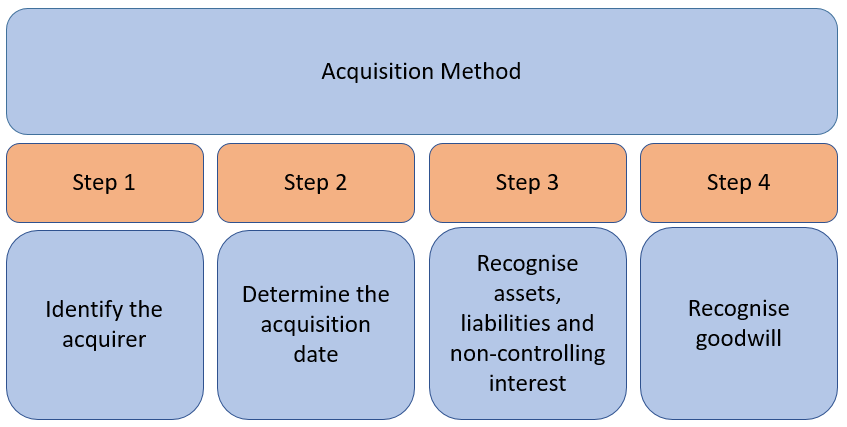

If the business combination meets the definition of an acquisition, then the four-step acquisition method is applied:

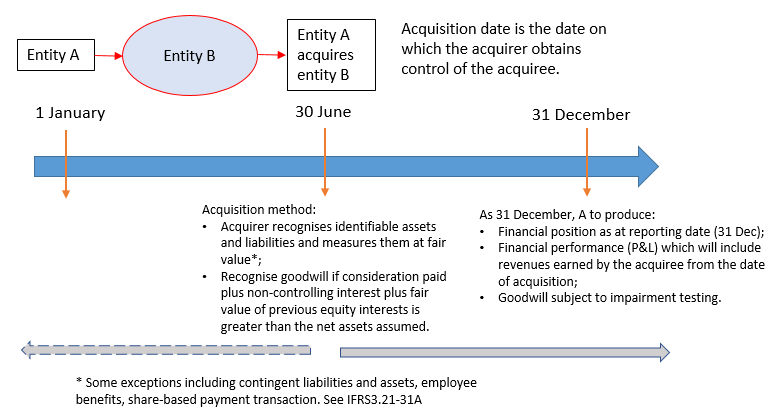

The acquirer, which is the entity that obtains control of the acquiree, will as at the acquisition date recognise the identifiable assets and liabilities and non-controlling interest at fair value. Assets that do not meet the separability criterion or contractual-legal criterion cannot be recognised separately; examples include potential contracts, synergy benefits, contingent assets.

Overview of acquisition by entity A acquiring entity B

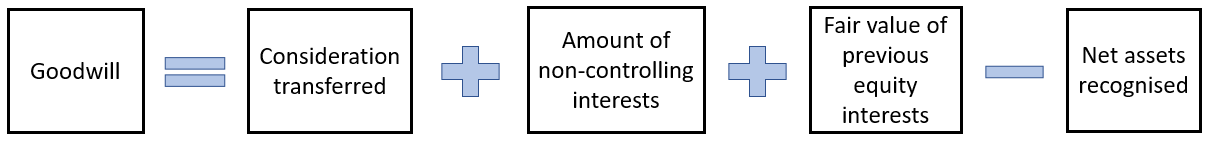

Unlike an amalgamation, the double entry to the assets and liabilities recognised by the acquirer will be recorded as goodwill.

The acquirer recognises goodwill which in simplified terms can be expressed as follows:

Goodwill is testing annually for impairment and it not amortised.

Conclusion

Both IFRS 3 and IPSAS 40 seek to improve the relevance, reliability and comparability of the information that a reporting entity provides in its financial statements about a business or a public sector combination.

While IPSAS 40 includes guidance for both amalgamations, including entities under common control, and acquisitions, IFRS 3 currently only provides guidance for acquisitions.

There is a conceptual basis for distinguishing between acquisition and amalgamation accounting. Acquisitions involve one entity taking over another entity and are fairly common in the private sector. The core concept is for the acquirer to fair value all identifiable assets and liabilities of the purchased entity and to recognise goodwill if the amounts paid for an entity are more than the fair value of the assets and liabilities.

An amalgamation, however, implies "business as usual" – the combined entity is fundamentally the same in both resources and service commitments and the financial statements should reflect the fact that the combination is a continuation, albeit with a different organisational structure.

Both the acquisition method and the pooling of interest method are designed to be applied in different scenarios, with the pooling of interest method best suited to machinery of government changes.